Comparative analysis

Kuldīga is proposed for World Heritage Listing as one of the few remaining and best-preserved historic urban centres representing a significant historic empire within the Baltic region – the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia (1561-1795). The town was an important urban centre during the time of the duchy and hosted key administrative institutions as well as economic and early industrial facilities. In order to provide a detailed understanding of all urban components in Kuldīga which either originated during the time of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia or had an important function in its administrative, economic and social dimensions, attribute mapping was conducted in the course of the summer 2019. The survey of the historic building fabric and urban structures identified several attributes which were researched and thoroughly mapped. A major focus was placed on different aspects of the urban layout and town structure, such as the street network, water bodies, green spaces as well as the location of religious, public, residential and auxiliary buildings. The streetscape along with the building facades formed a second category that was mapped and analysed, especially regarding the use of materials and architectural styles that give testimony to the craftsmanship and multicultural society of Courland. To a lesser extent, building interiors and vistas onto the town from different perspectives were taken into account. The results of the attribute mapping, the outcome of which can be seen in the maps, images of mapped facades and floor plans integrated in this nomination file, also provided a significant foundation for the Comparative Analysis in that the attributes which were recorded in Kuldīga represent the benchmark which would have to be matched or surpassed by comparative examples.

Methodology applied for the comparative analysis:

21. gadsimta sākumā, tiecoties pārskatīt Pasaules mantojuma sarakstu, Pasaules mantojuma konvencijas konsultatīvā organizācija ICOMOS veica pētījumu “Pasaules mantojuma saraksts: robu aizpildīšana – rīcības plāns nākotnei” (ICOMOS 2004). Šajā pētījumā organizācija izstrādāja trīs metodes, kā labāk klasificēt Pasaules mantojuma sarakstā un nacionālajos sarakstos iekļautās mantojuma vietas: tipoloģiskais ietvars, tematiskais ietvars un reģionāli hronoloģiskais ietvars (ICOMOS 2004, 5).

Considering the specific qualities of the property, which emphasises the significance of Kuldīga as the last remaining well-preserved urban testimony of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia based on criterion (iii), the Comparative Analysis was conducted predominantly following the Chronological-Regional Framework. At the same time, the comparative analysis integrates considerations which would feature in the typological framework in its focus on other urban centres which could illustrate similar attributes or also the thematic framework when considering its attributes presenting testimonies of international trade, political neutrality, migration and international cultural exchange.

The comparative analysis is developed in a three-step approach.

- Pirmā daļa tiecas salīdzināt citas Pasaules mantojuma sarakstā jau iekļautas mantojuma vietas, kā arī līdzīgas nacionālajos sarakstos iekļautas mantojuma vietas. Ir ļoti maz adekvātu piemēru, kur koncentrēta uzmanība uz specifisko reģionālo un laikaposma kontekstu. Lai gan varam norādīt uz dažām citām šajā nozīmē atzītām pilsētām, neviena no tām nav aktuāla tā vēstījuma kontekstā, kādu Kuldīga tiecas pārstāvēt.

- Otrajā daļā tiek aplūkotas citas reģionālās Ziemeļeiropā un Austrumeiropā laikā no 16. gadsimta nogales līdz 18. gadsimtam pastāvējušās varas, kam bija līdzīga struktūra, lai stiprinātu izvirzīto apgalvojumu, ka Kurzemes-Zemgales hercogiste izveidoja pietiekami nozīmīgas mantojuma liecības, lai tās tiktu atzītas globālajā mērogā un iekļautas Pasaules mantojuma sarakstā.

- Lastly, the third and perhaps most relevant part of the comparative analysis is focused on all sites that could potentially give testimony to the role and influence as well as life, urban and social structure of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia. This comparison is detailed and based on surveys in all other urban contexts, which may provide similar representations. The authors believe that this third section is most relevant in highlighting why Kuldīga is not only the best-preserved but strictly speaking the only property and historic centre, which can convey a complete testimony of this influential and lasting empire.

World Heritage properties and properties on national tentative lists

The World Heritage List counts a number of historic city centres already inscribed in the region of Europe and North America. In the region of Northern and Eastern Europe these include: Bryggen in Norway (1979), the Hanseatic Town of Visby in Sweden (1995), the Hanseatic City of Lübeck in Germany (1987), the Historic Centre of Riga in Latvia (1997), the Historic Centre of Saint Petersburg and Related Groups of Monuments in the Russian Federation (1990), the Historic Centres of Stralsund and Wismar in Germany (2002), the Historic Centre (Old Town) of Tallinn in Estonia (1997), the Naval Port of Karlskrona in Sweden (1998), Old Rauma in Finland (1991), and Vilnius Historic Centre in Lithuania (1994).

Out of these towns, only Bryggen was listed under criterium (iii), which recognises “unique or at least exceptional testimony to a cultural tradition or to a civilization which is living or which has disappeared”. The World Heritage property of Bryggen is recognised for the town’s ability to illustrate the urban setting of a 14th century trading hub of the Hanseatic League as the only remaining overseas Hanseatic Office. Even though the properties compare under the thematic framework in that both towns participated in international trade and were part of the Hanseatic League, this characteristic of Kuldīga does not contribute to the Outstanding Universal Value expressed in this nomination, as its development predates the period of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia. The urban setting and architectural style of Bryggen developed in an earlier timeframe and was shaped by a different political context.

Similar to Bryggen, a number of sites are listed with regard to their significance within the Hanseatic League, hence having a historical focus different from that of the nominated property. The Hanseatic City of Lübeck is recognised as the capital of the Hanseatic League which represents the typology of buildings constructed within this important time of trade in the Baltic Sea. The Historic Centres of Stralsund and Wismar, in addition to them representing the Wendish section of the Hanseatic League, further illustrate town development as administrative centres within the Swedish Kingdom as well as the specific use of Brick Gothic. The Historic Centre (Old Town) of Tallinn is recognised for the illustration of the international influences of a 13th to 16th century trading hub of the Hanseatic League in north-eastern Europe. The Hanseatic Town of Visby in turn represents a fortified trading centre in northern Europe of the Hanseatic League in the 12th, 13th and 14th centuries. While all of these sites share with Kuldīga the aspect of international trade, they focus on a cultural phenomenon, specific time frame and political representation different from the one emphasized by Kuldīga / Goldingen in Courland.

In addition, there are few historical urban centres representing different political entities contemporary to the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia, such as the Kingdom of Sweden and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. The Naval Port of Karlskrona testifies to the urban layout of a 17th century harbour in the Swedish Kingdom, which illustrates the military intentions of this political empire. The Historical Centre of Riga was an important town of the Hanseatic League in the 13th to 15th centuries and the largest provincial town of Sweden in the 17th century. Its Outstanding Universal Value however expresses the creative human genius of different architectural styles, such as 19th century wooden architecture and its significant Art Nouveau buildings. The Historic Centre of Saint Petersburg and Related Groups of Monuments was built in the 18th century under the eastern neighbour of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia, the Russian Empire. It represents significant achievements of the empire with regard to urban design and architecture, such as its exceptional examples of baroque palaces. The Vilnius Historic Centre bears testimony to the capital of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania that bordered the Duchy of Courland in the south. Rather than focusing on specific centuries, here the Outstanding Universal Value is justified in the continuing successive layers which formed the capital over a period of nine centuries.

Finally, the city of Old Rauma in Finland is inscribed entirely based on its role for the typology of northern European towns, especially regarding vernacular wooden architecture. While this town has preserved similar specific craft skills that likewise continue to be used, its attributes are focused on the specific typology of architecture rather than the economic and political context in which it emerged. In chronological terms, the large majority of Rauma’s exceptional wooden architecture was created in the late 18th and 19th centuries. Kuldīga, in contrast to Old Rauma, does not focus on a typology of architecture but on an urban ensemble testifying to a historic society. The specialists at the World Heritage property of Old Rauma however are a strong partner of the Kuldīga Restoration Centre and frequent exchanges take place between the properties.

Reviewing the presently listed World Heritage sites, only one was found which has a link with the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia: Kunta Kinteh Island and Related Sites (listed in 2003 as James Island and Related Sites under criteria (iii) and (iv)) in Gambia. Kunta Kinteh Island (or James Island) is the place where Jacob Kettler (often also referred to as James Kettler) established the ducal colony from which he exported goods to the Americas. The island and several other related sites on the banks of the Gambia River were listed because they “provide an exceptional testimony to the different facets of the African-European encounter, from the 15th to 20th centuries. The river formed the first trade route to the inland of Africa, being also related to the slave trade.” (UNESCO 2012, 71). Therefore, the listing of the site reflects the significance of the Duchy of Courland only fragmentarily and thus the World Heritage site does not represent a barrier to a World Heritage initiative focussing on it.

Currently, a total of six cities are inscribed on the World Heritage List based on the use of criterium (iii) without the addition of further criteria. Out of the recognised sites, three are located in the UNESCO region of Europe and North America, and one each in the Arab States, Asia and the Pacific as well as Latin America and the Caribbean. These sites are: Bryggen in Norway (1979), the Old City of Berne in Switzerland (1983), San Marino Historic Centre and Mount Titano in San Marino (2008), Punic Town of Kerkuane and its Necropolis in Tunisia (1985), Historic City of Ayutthaya in Thailand (1991), and Historic Quarter of the Seaport City of Valparaíso in Chile (2003). Given the specific regional and time frame of the narrative of the nominated property, only the European examples were considered for comparison.

While Bryggen was already described above, the two remaining European towns recognised under criterion (iii) shall be mentioned. The Old City of Berne illustrates the integration of the historical core of the city into the urban fabric of the contemporary capital of Switzerland. In this, it compares to Kuldīga as an urban and administrative centre that preserved historical urban fabric from medieval times and successfully integrated them into the modern cityscape. San Marino Historic Centre and Mount Titano represent an important stage of political development that is illustrated by the continuity of urban spaces. The political entity established in San Marino in the 13th century still exists today and hence had a lasting impact on the society of this specific city-state. However, both properties represent the region of Western/ Mediterranean Europe and hence do not necessarily hold the ability to testify to similar developments in the Baltic states. This aspect also mirrors in the attributes of the towns that differ from the architecture that evolved in Kuldīga during the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia.

The historic towns and cities that are on national tentative lists mostly testify to a different regional context, as they are located in Kenya (The Historic Town of Gedi), Indonesia (Historical City Centre of Yogyakarta), Republic of Korea (Naganeupseong, Town Fortress and Village), Yemen (Historic City of Saada and The Historic City of Thula), Ireland (The Historic City of Dublin), Portugal (Historical Lisbon, Global City and Vila Vicoa, Renaissance ducal town), Turkey (Historic City of Harput, Historic Town of Beypazari, Historic Town of Birgi) and Mexico (Historic Town of Alamos and Historic Town of San Sebastián del Oeste). Out of these sites, only Vila Vicoa, Renaissance ducal town is relevant for a comparison as it describes an urban centre of a duchy and the continuation of this heritage until today. However, it emerged in an entirely different context, due to its location in southern Europe and an earlier time frame, beginning in the 14th century.

Only three historic towns listed on national tentative lists belong to the same region as Kuldīga. The Lithuanian property of Trakai Historical National Park includes the town of Trakai and its role as a defensive centre of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in the 13th and 14th centuries. The site is proposed as a mixed property. The narrative proposed for Gdansk - Town of Memory and Freedom in Poland connects to the typology embodied by its architectural and urban heritage of the 16th and 17th century as well as strong intangible associations with freedom movements. Finally, the Belarussian tentative list includes Worship wooden architecture (17th – 18th centuries) in Polesye. While this site shares with Kuldīga architectural remains of a similar timeframe, the architectural style described in this property is entirely focused on wood and developed in the specific context of religion.

In addition to the town of Kuldīga – the subject of the World Heritage nomination representing the Duchy – Latvia has listed only two sites its Tentative List for future World Heritage nominations: The Meanders of the Upper Daugava, a mixed site unrelated to the Duchy of Courland and outside of the former territory, as well as the site of Grobiņa Archaeological Ensemble (UNESCO 2019). The town of Grobiņa was included in the survey for the Comparative Analysis due to it having been a seat of captain during the period of the duchy and due to its general relevance as a fortification point along the Hellweg.

In conclusion, the comparison of Kuldīga/Goldingen in Courland with similar sites on the World Heritage List as well as on national tentative lists shows that no other property currently exists that can convey the narrative of the development of urban centres of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia. In fact, the existence of representative historic urban centres of all of the surrounding political empires strengthens the argument for an inclusion of the perspective of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia onto the World Heritage List, to complete the diverse perspectives onto Baltic history of the 17th and 18th centuries.

Regional powers in northern and eastern Europe (16th-18th century)

The detailed examination of the history of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia demonstrates that although it was never an independent state during its existence, several dukes of Courland were able to establish themselves as almost autonomous rulers. This is particularly the case for the 17th century as well as for the brief first rule of Duke Ernst Johann Biron in the mid-18th century. As a result, the dukes – most notably Duke Jacob Kettler and to a lesser degree his son Friedrich Casimir – could pursue mercantilist policies to encourage early industrial development based on iron processing, for which they built the required facilities. The iron ore required for this process was either mined locally or imported from abroad (Jakovļeva 1993, 102-03, 105). The ability to produce canons, nails and other materials in turn supported the local ship-building industry in Ventspils which was one of the foundations for the extensive sea trade, the colonial schemes, and thereby the international recognition of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia in the 17th century. The dukes of Courland had their own envoys in the main cities and ports of the time through which they negotiated trade agreements as well as dynastic relations through marriage with the European heads of state of their time.

In this, they were set apart from the other entities in the Baltic region which were not nearly as independent. The Duchy of Livonia, situated north of the Daugava River (Vidzeme and Latgale) and reaching into southern Estonia, became a province of Poland-Lithuania following the secularisation of the Livonian Order in 1561 (Jakovļeva 1993, 127). In 1621, the territory fell under Swedish control when King Gustav II Adolf conquered it (Hoensch 1998, 135). As part of the Truce of Altmark, signed in 1629, Livonia was officially recognised as a Swedish province. Compared to the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia, the Livonian iron works were much more limited in number (Jakovļeva 2019, 104-05). When the Russian troops defeated the Swedish at Poltava in 1709 and Swedish King Karl XII had to abandon Livonia, Czar Peter the Great took control of the region (Hoensch 1998, 158-59) and maintained it until Livonia was confirmed as a Russian province under the Treaty of Nystad in 1721, which represented the official end of the Great Northern War. Throughout this time, the Duchy of Livonia was not ruled by a dynastic family but rather by governors who were put in place by the respective overlords. Thus, Polish / Swedish Livonia could not flourish as well as the Duchy of Courland did in the 17th century.

In the wider European context, duchies were a common political system since medieval times. However, a comparison of a majority of the duchies, and the few authentic remains of their urban centres, with Kuldīga and the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia does not seem appropriate for various reasons, such as a different timeframe (for example for the Duchy of Pomerania which ceased to exist in 1637) or a different political status (such as the Duchy of Silesia, which was a province of Poland with considerably less political and economic influence on a global scale). The situation was slightly different for the Duchy of Prussia which was established in 1525 when Albrecht of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Master of the Teutonic Order and a member of the Hohenzollern family, swore allegiance to the Polish king. In fact, the constitutional structure of ducal Prussia was more similar to the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia which followed the Prussian example. The rule of Albrecht and his (male) heirs was granted for as long as the direct male line remained unbroken. However, Albrecht’s successor – his son Albrecht Friederich – suffered from a mental illness which did not allow him to govern the Duchy of Prussia independently (Clark 2007, 30), so that a regent was appointed to rule for him. As a result of the relations with the Polish king, whose sister the duke of Brandenburg had married in 1535, Joachim II managed to have his two sons recognised as potential heirs of the Duchy of Prussia in case Albrecht Friederich would die without male heirs of his own. In the following decades, the Hohenzollerns of Brandenburg managed to slowly build and strengthen their claim on the Duchy of Prussia, using both marital policy (the marriage of Johann Sigismund to Anna of Prussia, daughter of Albrecht Friederich in 1594, see Clark 2007, 30) and the need for a regent for the duchy (appointment of Duke Joachim Friederich of Brandenburg in 1603, see ibid.). When Albrecht Friederich finally died in 1618, leaving only two daughters, the Polish King granted the Duchy of Prussia as a fief to the House of Brandenburg (Hoensch 1998, 103). During the first Northern War (1655-1660), Brandenburg fought on both sides, first on the side of Swedish King Karl X and from 1658 onwards for Poland and Austria. In order to secure an alliance with Brandenburg, Karl X promised duke Friedrich Wilhelm of Brandenburg full sovereignty over the Duchy of Prussia in 1656 (Clark 2007, 73). As part of Poland-Lithuania’s efforts to secure Brandenburg’s military support for their side, the Polish King granted Brandenburg full sovereignty in the secret Agreement of Wehlen which both parties signed in 1657 (Clark 2007, 74). In terms of international law, however, the Duchy of Prussia was still part of Poland-Lithuania until 1773 when the then Kingdom of Prussia and Poland-Lithuania signed an agreement effectively ending Prussia’s vassal status and granting full legal sovereignty (Hoensch 1998, 165). In light of the historical changes since the death of Duke Albrecht of Brandenburg Ansbach, it can be stated that the Duchy of Prussia was controlled from the early 17th century by the Hohenzollerns of Brandenburg who had established their ancestral seat in Berlin, i.e. outside of the Baltic region. This supports the conclusion that the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia, particularly during the rule of the Kettler dynasty, represents the only political entity located in the Baltic region from the mid-16th to the 18th century which could foster broad economic progress and act quasi-independently in relations with other European powers.

As the comparison with other contemporary political entities shows, Prussia is the only Duchy which is comparable to that of Courland regarding its economic and political independence. Both duchies were internationally recognised at the time and produced achievements far greater than those of similar political entities. With regard to Prussia, its outstanding accomplishments have been acknowledged on the World Heritage list since 1984, when the Castles of Augustusburg and Falkenlust at Brühl were inscribed under criteria (ii) and (iv). In the following years, multiple sites representative of Prussia were added to the World Heritage list, namely, the Palaces and Parks of Potsdam and Berlin (1990) and the Museum Island in Berlin (1999).

Following this argumentation, and acknowledging that the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia was even further advanced than the Duchy of Prussia regarding aspects of international trade, the authors consider it justified that the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia may be recognised as UNESCO World Heritage, especially when pursuing the historical-regional approach as it was established by ICOMOS in the study “Filling the Gaps” (2004).

An indication for the international reputation of Courland in the 17th century, which no doubt represents the culmination of the duchy’s significance in Europe, can not only be found when reviewing the history of the duchy, but also in a failed but intriguing initiative in the late 17th century. William Penn, an Englishmen born in 1644, leader of the Quaker movement and the founder of the Federal State of Pennsylvania (Tolles 2019), developed an idea for a European organisation essentially promoting peace on the continent. In An Essay Towards the Present and Future Peace of Europe (published 1693), he not only explained the concept and structure for this organisation, but also noted down the European powers who should partake in “Sovereign Part, or Imperial State” (Penn 1693, 408) and specified their proposed number of votes. Courland, together with the duchy of Holstein, formed the smallest entities unified in the organisation with each having one vote (Penn 1693, 409). While William Penn’s idea was not realised, his proposal shows that the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia was recognised as a relevant part of Europe at the end of the 17th century.

Regional comparison in the urban context

The methodology of this third section of the Comparative Analysis was chosen in a way that does not seek to compare Kuldīga as a representative of a specific urban typology, which would require further comparison of additional towns in broader Europe and the Baltics, for example in the former Duchy of Livonia, made up of the Latvian region of Vidzeme as well as Estonia. Urban centres of Livonia, such as Cēsis and Limbaži in northern Latvia, partially feature similar architecture as Kuldīga. However, the Outstanding Universal Value of Kuldīga lies within its ability to represent the narrative of a residence and important administrative centre of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia and the urban expression of its political autonomy, international trade and intercultural relations. That said, the towns in this comparison were chosen with regard to their role within the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia as well as their respective ability to testify to the ducal time by the means of historical urban fabric. The urban development of the aforementioned Livonian examples is embedded in an entirely different historical context than Kuldīga and is therefore irrelevant for the focus of this analysis. Instead, the Comparative Analysis aims at an analysis of the entire remaining heritage of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia to illustrate that Kuldīga is the best-preserved and most diverse existing testimony to this significant period of history.

Kuldīga was the residence of the ruler Duke Gotthard and prime administrative centre at the time the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia was established in 1561. During the later shared reign of Wilhelm and Friedrich Kettler, the Duchy of Courland was placed under the authority of Wilhelm Kettler whose residence continued to be located in Kuldīga. His brother Friedrich on the other hand, was given Semigallia and Selonia and resided in Jelgava. After the end of the shared reign of the Kettler brothers, once Wilhelm Kettler had been removed from power and had to go into exile, the official residence of the Duke of Courland was fully established in Jelgava.

As part of the consolidation of the Duchy following Wilhelm Kettler’s exile, the aforementioned Formula Regiminis was adopted which among other things established a new administrative system. As a supreme district (ger. Oberhauptmannschaft), Kuldīga became one of four administrative and judicial centres of the Duchy. Besides Kuldīga, these were established in the towns of Jelgava and Tukums, as well as the former order castle at Sēlpils. Subordinated to each supreme district were several lower districts. The following districts initially belonged to Kuldīga: Ventspils, Durbe, Skrunda, Saldus, and Grobiņa.

Besides the other supreme districts and the subordinated districts belonging to Kuldīga, the following cities were included in the survey: Liepāja was an important port town which rose to significance in the late 17th century when part of the long-distance sea trade was being conducted from its harbour. The town of Jēkabpils / Jakobstadt was given its name by Duke Jacob Kettler in the 17th century when he awarded the former settlement town rights. It had its origin in the settlement Sloboda which was mainly inhabited by war refugees and Old Believers who had emigrated from Russia. Bauska was an important town during the reign of Gotthard Kettler. The Diet (ger. Landtag), a constitutional assembly of the duke and the members of nobility, was held twice per year, one in summer in Jelgava and one in winter in Bauska. Altogether, the Diet was held five times at Bauska Castle from 1571 onwards.

The towns presented in the Comparative Analysis will be presented alphabetically.

Aizpute / Hasenpoth

On the right bank of the Tebra / Tebber River, a Couronian castle had been erected which was conquered by the Teutonic Order in 1245. The Order built a second castle on the opposite river bank in 1249. When the land was divided between the bishop and the Teutonic Order in 1253, the land on the right river bank was distributed to the Bishopric of Courland, while the land on the left bank was given to the Teutonic Order. In 1378, Aizpute (56° 42' 56.66" N 21° 36' 19.098" E) was given town rights, awarding the town a mayor and a town council. Aizpute did not have independent guilds, however; the guilds were subordinated to the guilds in Kuldīga. Aizpute became a part of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia in 1611, after it had been temporarily pawned to the Margrave of Brandenburg. Aizpute became a subordinated district to Kuldīga, but was later joined with Grobiņa to form a supreme district in the 19th century.

An interview with Signe Pucena, researcher of traditional culture and culture projects manager of the non-governmental organization Interdisciplinary Art Group SERDE, revealed that the rivers Tebra and Saka / Sacke were still navigable by boat in the medieval period, which allowed for the construction and use of a harbour near Kuldīgas Street. The construction was funded by the citizens of Aizpute who also provided the funds for storage buildings. The Saka, however, was closed for navigation in 1656, a ruling which was confirmed by the Peace of Oliva in 1660. In the 18th century, Aizpute was in direct trade competition with Liepāja, where a large harbour had been constructed

The historical urban fabric of Aizpute largely represents the 19th century. However, there are a number of buildings which date to the period of the duchy and even before that. These include the ruins of the Teutonic Order castle. The building showcases both its origins as a fortified castle constructed in 1276-1290 (Zarāns 2006, 8) as well as the later extensions and remodelling during the late 16th to early 17th century (Alttoa et al. 1992, 356). Another significant building is St. John’s Lutheran Church overlooking the lakes and in direct line of sight to the castle. As Signe Pucena further explained, before the town was incorporated into the duchy, Aizpute had been part of the land controlled by the bishop of Courland since 1253 and had been the seat of the bishop until the 16th century when the former bishop’s castle had been destroyed by Polish troops in 1583. A large memorial stone slab which was found in the church in the 19th century commemorates Bishop Heinrich von Basedow who died in Aizpute in 1523. The Lutheran church was built on the foundations of the castle. By 1623, it had fallen to ruins again and had to be re-built in 1698/99. After the roof collapsed in 1720 and damaged large parts of the church’s interior, its restoration was completed again in 1733. The benches, the altar and the pulpit were consecrated four years later.

In terms of the urban layout, the street network documented in historic maps has changed and important urban spaces, such as the old market square on the road to Jelgava, no longer exist or are hardly recognisable. The overall setting of the town and the definition of the urban landscape by the castle and the church as well as the river, the lakes and the bridges, continue to shape the perception of the small town. Unfortunately, little information is available to assess the building stock in Aizpute. The two synagogue buildings from the early 19th century have been preserved, but were joined together and are presently used as a cultural centre. The local NGO SERDE has chosen to establish their headquarters in a building which originates from the 17th century and was extended several times in the 18th century. While the survey team visiting Aizpute observed further buildings which might (originally) date to the 17th to early 19th century and thus would constitute architectural heritage relevant to the scope of this study, their construction dates cannot be ascertained.

Bauska / Bauske

Bauska (56° 24' 37.037" N 24° 11' 59.996" E) is the site of a castle of the Teutonic Order which was built in the 15th century as one of the last stone castles (Zarāns 2006, 80) and served as the seat of a bailiwick (ger. Vogtei) and as a border fortification towards Lithuania in the south. Near the castle, a small settlement grew which was pledged to the king of Poland in 1559 and transferred to the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia in 1563, after Archbishop Wilhelm of Riga, who had been in charge of it until then, had died. In 1584, the settlement was moved to the left bank of the Memel River, where it still exists today. Town rights were awarded to Bauska in 1609. The town later became one of the captains’ districts belonging to the supreme district in Jelgava. Due to its location along the southern border of the duchy, Bauska was involved many times in military conflicts with Poland, Sweden and Russia in the 17th century. The decline of the town was further aided by the plague which resulted in a massive loss of the population of the duchy in 1710. Bauska’s location on the trade route between Riga and Lithuania encouraged trade in cereals, linseed and flax, as well as with vegetables and fruit.

Today, the ruins of the Bauska castle, which have largely been preserved in the state of the years 1443 to 1456, can still be observed. The castle was further fortified by Duke Friedrich in the late 16th century (Zarāns 2006, 80). He also had the adjoining palace constructed in Renaissance style. The exterior of the palace façade was decorated with a Sgraffito design which can also be found on southern German palaces (Alttoa 1992, 358). In 1706, the castle and palace were destroyed by Russian troops. Since the 19th century, there have been several restoration and reconstruction programmes. As a result, the palace was rebuilt fully and the castle ruins were also altered. In an interview that was conducted in the course of a comparative analysis survey in preparation of this nomination file, the director of the Bauska Castle Museum stated that, presently, the main tower is being reconstructed in order to stabilise the complex and to prevent deterioration due to water erosion.

Aside from the castle ruins, Bauska has preserved its town hall, the construction of which was begun in 1616 (Putniņa & Bākule 2011, 13). A building survey conducted in the year 1840 indicated that the mayoral hall had been rebuilt in the 18th century and its exterior had been altered significantly (Putniņa & Bākule 2011, 17). Due to the state of disrepair which the town hall was in the middle of the 19th century, the city council decided to abandon the building. The tower was torn down, the second floor was removed and the rest of the building was used for shops and warehouses (ibid.). Until 2011, a major reconstruction project was completed as a result of which the town hall was rebuilt in accordance with the state documented in the mid-19th century. A third key building of the town structure during the period of the duchy is the Church of the Holy Spirit which was first constructed from 1591 to 1594 and further remodelled in the 18th and 19th centuries. It represents a striking example of a Lutheran church which in its design rejects the rich decorations of Catholic churches (Alttoa 1992, 358). In the years 1614-23, the bell tower was added on the western façade of the building. In the 17th century, the tower was crowned with a dome which was replaced by the present roof in 1813 (Alttoa 1992, 358). In its interior, the church showcases a few artistically valuable pieces which date to the period of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia. These include the pulpit, the prospect of the organ and the confessional from the 18th century (all in the Rococo style), the epitaph of J. Henning (1677), choir stalls with decorations (1688) and a carved lectern (1689).

The street layout of the Old Town of Bauska has remained fairly intact which is evident when comparing the present street network with historical maps, such as the town map dating into the year 1797. Key monumental buildings, such as the castle, the church of the Holy Spirit or the Town Hall are mapped there as well. Naturally, Bauska has grown significantly beyond the town limits during the times of the duchy. More relevant is the question of the preserved urban fabric and the dating of individual buildings in the old town. Fortunately, the survey for the Comparative Analysis had access to a map providing this data which was the result of a building survey in 2012/13. The survey found that 23 buildings still displayed architectural details dating to the time before the year 1797 and could indeed be identified on the town map which was produced that year. Reviewing the present state of these buildings, however, it has to be stated that several of these buildings represent later and oftentimes modern architectural elements which weaken their authenticity. Based on observations during a visit to Bauska, the authors believe that no more than 15 buildings retained sufficient authenticity to represent the time of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia. The western part of Rīgas Street proves to hold one of the most authentic streetscapes of Bauska, with a high density of residential buildings of the ducal era in one block. In addition, the old town includes a high proportion of 20th century architecture, particularly west of the Church of the Holy Spirit as well as south of Plūdoņa Street and east of Kalēju Street.

Durbe / Durben

The town of Durbe (56° 35' 12.487" N 21° 21' 55.526" E) is located on the banks of the lake with the same name. In 1253, during the division of land between the bishop of Courland and the Teutonic Order, Durbe became part of the dominion of the Order which erected a castle in the first half of the 14th century. In the 15th century, a small settlement was formed which was soon lost to a fire, but was rebuilt again. During the times of the duchy, Durbe remained a hamlet and did not receive town rights. However, it was a subordinated district belonging to the supreme district of Kuldīga. During the invasion by Russian troops at the beginning of the 18th century, Durbe Castle and the hamlet were completely destroyed.

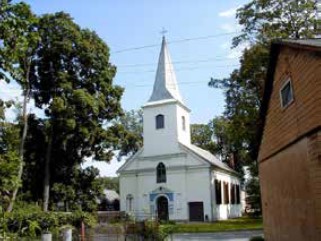

The remains of the castle can still be visited today, though they consist only of the castle mound and few elements still standing upright. Little has been preserved of the hamlet which had been rebuilt in the 18th century. The Lutheran church, on the other hand, which was built in 1651 and renovated in 1847/72, can still be observed today.

Grobiņa / Grobin

Similarly to Durbe, the town of Grobiņa (56° 32' 22.675" N 21° 10' 0.811" E) formed in the vicinity of a castle of the Teutonic Order which had been built in 1245. However, this castle was conquered by the Couronians in 1260 and destroyed by the Order when it re-conquered it in 1262. As Grobiņa is located on the trading route running from Riga to Königsberg in the west, called Hellweg, the location remained an important fortification point (Pirang 1926, 35, 64). Therefore, the castle was rebuilt in 1290. The settlement of Grobiņa would only form later, in the middle of the 15th century. From 1560 to 1609, the hamlet was pawned to the duke of Prussia in order to raise funds for the war against Russia. Soon after its return into the dominion of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia, as part of the dowry of Princess Sophia of Brandenburg when marrying Wilhelm Kettler, Grobiņa became one of the districts subordinated to the supreme district of Kuldīga. In 1659, the hamlet was conquered by Swedish troops and burnt down. In 1695, Grobiņa was awarded town rights. Records from the early 18th century report that the raging pestilence heavily impacted the town which lost all but eight of its citizens.s dzīvi palika tikai astoņi tās pilsoņi.

While Grobiņa was part of Prussia, the trade with Poland-Lithuania prospered. Several craftsmen settled in the town, such as a hat maker, an amber craftsman, and a weaver. Today, little is preserved of the buildings of the 17th and 18th centuries. The ruins of the former Teutonic Order castle – though altered during later centuries and also by modern restorations – can still be observed. Opposite the castle ruins, a Lutheran church constructed in the 17th century has survived.

Jaunjelgava / Friedrichstadt

Jaunjelgava (56° 36' 44.316" N 25° 4' 44.137" E) formed much later than most towns which existed during the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia. The settlement was created in the late 16th century during the Swedish-Polish War and was given town rights in 1630 (Lexikon Baltische Ortsnamen II, 175). A new phase of growth and development was initiated in 1646 by Dowager Duchess Elisabeth Magdalene, and the town was subsequently re-named after her late husband, Duke Friedrich Kettler.Lexikon Baltische Ortsnamen II, 175). Jaunu tās izaugsmes un attīstības posmu 1646. gadā uzsāka atraitnēs palikusī hercogiene Elizabete Magdalēna, un pilsēta tika nodēvēta par godu viņas nelaiķa vīram hercogam Frīdriham Ketleram.

As Jaunjelgava is located on the banks of the Daugava, it was one of the transfer places for goods from land to water transport. The town traded wheat and flax, and in the 18th century, it housed a hat maker, a tavern and a processing plant for tobacco (ibid.).

Jēkabpils / Jakobstadt

Jēkabpils (56° 30' 5.238" N 25° 52' 41.876" E) was founded in the 17th century as a settlement of Old Believers who had fled Russia, as well as Polish war refugees. When Duke Jacob Kettler awarded the hamlet, which was then known by the name Sloboda, town rights in 1670, he also changed its name to ‘Jakobstadt’. In 1708, the town was destroyed almost completely by a fire after it had been conquered and plundered by Polish troops. The number of inhabitants was further decimated by the pestilence in the year 1710. Due to the origin of the town, only Russian or Polish citizens could initially be elected as mayor, which is a peculiarity in the Duchy of Courland of Semigallia.

Similarly to Kuldīga, the town of Jēkabpils was an important trading place for the transport of goods which were transferred from land to water. The reason for this lies in the existence of rapids in the Daugava that were located south of the town and interrupted shipping on the river.

In Jēkabpils, there are only three burgher houses from the 19th century which are listed as monuments. Furthermore, St. Michael’s Lutheran church built from 1769 to 1807 as well as a Roman-Catholic church dating from 1756 are preserved. The presence of several Christian faiths is further exemplified through the existence of an Orthodox church from 1783, the Nikolai monastery, and synagogues (Lexikon Baltische Ortsnamen II, 240).

Jelgava / Mitau

Like most other towns in the Duchy, Jelgava (56° 39' 3.992" N 23° 43' 16.874" E) had its origin near a castle of the Teutonic Order which was built in 1265. The hamlet which developed in its vicinity received town rights in 1573 and established a town council and guilds. In 1578, Duke Gotthard Kettler selected Jelgava as his residence and settled in the castle. While Kuldīga still remained an important residential town during the reign of Duke Wilhelm Kettler (1596-1616), his exile firmly established Jelgava as the primary residence of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia. Jelgava was also one of the four supreme captains’ districts which oversaw the districts of Dobele / Doblen and Bauska. As the main ducal residence, Jelgava found itself at the centre of all military conflicts and was conquered and plundered several times during the Swedish-Polish Wars in the first half of the 17th century. During the Nordic War, Jelgava was conquered both by Swedish and Russian troops. During the plague of 1710, the town lost about one third of its inhabitants.

As the main residence of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia, Jelgava was a centre of the ducal monumental building programmes. The Teutonic Order castle and the ducal palace of the 16th century, which had served as ducal residence, were ordered to be demolished by Duke Ernst Johann Biron in 1737 (Zarāns 2006, 112). In its place, the duke commissioned the St. Petersburg-based architect Francesco Bartolomeo Rastrelli with the construction of a new palace which was built parallel to the duke’s future summer residence in Rundāle. Similarly to Rundāle, the palace was originally designed as a main building framed by two wings which formed a courtyard. Beneath this courtyard, the crypt of the Courland dukes was placed, though removed in 1820 (see below). As Duke Ernst Johann Biron was exiled from 1740 to 1762, Jelgava Palace was only finished after he had been restored as ruler of the Duchy. The palace had another famous inhabitant after Ernst Johan’s son and successor Peter Biron had left the Duchy of Courland – Louis XVIII of France, who after fleeing the revolution, resided in Jelgava from 1798 to 1801 (Zarāns 2006, 112). To this day, Jelgava palace remains the largest Baroque palace in the Baltic countries (Alttoa 1992, 364). During his rule, Peter Biron ordered the founding of a local academy, the Academia Petrina, which was modelled in accordance with a university. For the building of the academy, the architect Severin Jensen re-designed the former residence of the Dowager Duchess and later tsarina Anna from 1773 to 1775 (Alttoa 1992, 364) in the Late Baroque style.

Unfortunately, the former splendour of Jelgava can no longer be observed as the town was massively damaged during the Second World War. In 1944, the front line between German and Soviet troops ran near the town for three months and resulted in large-scale destruction. For this reason, the cityscape is dominated by Soviet and modern architecture with few historic buildings remaining from the times of the duchy. Jelgava Palace burnt out and was reconstructed from 1956 until 1964 (Alttoa 1992, 365). The reconstruction included an additional building component which had been erected in 1937, between the two wings, effectively closing off the courtyard.

Also, the building has been undergoing major restorations since the beginning of the millennium. The interior of the 18th century has, however, been largely lost. Currently, it is used as the seat of the Latvian Agricultural University. Also, the building still houses the coffins and most of the human remains of the Courland dukes, though no longer in the original crypt but in a subterranean room in the south-eastern building corner. The Academia Petrina was also heavily damaged by fires both in 1919 and in 1944. Its outer facades were restored according to their documented appearance in the 19th century in 1947-51. Today, it houses the Jelgava History and Art Museum. Academia Petrina smagi cieta ugunsgrēkos 1919. un 1944. gadā. Tās fasādes tika restaurētas 1947.–1951. gadā, atgriežot ēkai 19. gadsimtā dokumentos fiksēto izskatu. Šodien tur atrodas Jelgavas Vēstures un mākslas muzejs.

In addition to the ducal monumental buildings, several churches have been preserved. The Lutheran St. Anne’s Church was built in the 17th century (the tower in 1619-1621 and the church hall in 1638-41, see Alttoa 1992, 363). Since the church was re-modelled several times over the centuries, including after it had burned down in 1944, only the ground plan and very few architectural details of the original design have survived (Alttoa 1992, 364). Another surviving sacral building is Trinity Church. It also originates from the 17th century, but was massively damaged in 1944. Historian Andris Tomašūns writes that after a partial reconstruction in 2010 which complemented the remaining historic structures with a glass addition, Trinity Church today functions as a museum and a library. From the 18th century, the Church of Saint John and the Reformed Church are also preserved.

Of the urban fabric from the 16th to 18th centuries, i.e. the period of the duchy, only a scant number of buildings were preserved until today. These buildings are located in one of the last streets having preserved the former streetscape, Vecpilsetas Street. At the time of the survey, building No. 14 on this street was in the process of a major restoration and the survey team was invited to visit the building. The building was positively identified on a map from the 17th century and is likely the oldest house preserved in the street, but according to Andris Tomašūns was extended and altered in the 18th and 19th centuries.

The survey confirmed what the desk research had already foreshadowed: despite it being historically more important than Kuldīga – considering it was the only residence of the duke after 1642 – Jelgava suffered great damage over the centuries and no longer has enough historical urban fabric conserved to reflect the achievements of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia.

Kandava / Kandau

In 1245, the Teutonic Order conquered the Couronian castle mound which existed at the location of Kandava (57° 1' 59.344" N 22° 46' 36.444" E). The order erected one of its own castles around 1300, in the vicinity of which a settlement formed later on. This settlement grew into a hamlet which became a district subordinated to the supreme district of Tukums in the 17th century. However, during the times of the duchy, Kandava did not receive town rights. The town was conquered by the Swedes both in 1659 and 1703/04. Kandava’s economy at the beginning of the duchy was mainly based on craftsmen. Under the reign of Duke Jacob Kettler, a powder mill and a charcoal pile were established.

Kandava features an authentic urban structure which contains a number of buildings from the 16th to the 19th centuries. Among these are the Lutheran church with a chapel from the 18th century, both overlooking the historic centre from the so-called ‘Plague Hill’. Plague Hill was an ancient burial ground where excavations during World War II revealed skeletons from the 14th to 16th centuries as well as coins from the 18th century.

The Teutonic Order castle was still used for residential purposes until the mid-18th century. In the 19th century, however, the building began to fall in ruins until its walls were dismantled in 1840. Today, only ruins can be observed, though the location still houses the remains of the powder mill. The location of the Market Square as well as Sabiles and Lielā Streets date back to medieval times. Similarly to Kuldīga, a massive fire destroyed a majority of the log buildings of Kandava in 1870. Yet, the streetscape of Kandava is well-preserved compared to other towns, as it did not have to face significant loss of building stock through wars.

In 2011, the project “Restoration and tourism infrastructure development of the Old Town centre of Kandava” was executed. It was a project co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund.

Liepāja / Libau

The town of Liepāja (56° 30' 16.805" N 21° 0' 38.902" E) has its origin in the former fishing village of Liwa which existed on the banks of the river with the same name. In the division contract between the bishop of Courland and the Teutonic Order, it was established that the small harbour would belong to the bishopric while the hinterland was under the control of the order. In the 15th century, records for the first time mentioned the existence of a settlement with a market. Together with Grobiņa and other settlements in the southwestern region of Courland, Liepāja was given to Prussia for almost 50 years (1560-1609), in exchange for urgently needed funds to expel the Russian troops from the Duchy. As part of the dowry of the Prussian duke’s daughter Sophie who married Wilhelm Kettler, the region fell back to the duchy. In order to prevent Liepāja rising as a port town and becoming a competitor to Memel, the Prussian duke had withheld town rights. These were only granted after the return into the duchy, in 1625. With the town privileges, Liepāja received guilds and a town council. Due to its location close to the Polish-Lithuanian border, it was involved in several conflicts in the 17th century. In the Seven Years’ War, it was conquered by Russian troops, but following the turn of the war, also had to house Saxon and Swedish troops.

Liepāja’s great significance lies in its location along the western shoreline of the duchy, thus giving access to the Baltic Sea and consequently to the trade network towards the west. Together with Ventspils, it was one of the most important harbours in the Baltic region and thus of particular value to the duchy, but also later on to the Russian Empire. Unlike Rīga, it had the key advantage that it remained ice-free for most of the winter, thus keeping up sea trade all year long. The Kettler dukes, particularly Duke Jacob Kettler, recognized this advantage and supported the construction of a harbour in the town in the 17th century. The harbour was extended and deepened from 1697 to 1703, largely funded by the town’s citizens themselves. Trade further prospered when the harbour was deepened and piers were constructed in 1737.

From the period of the duchy, several buildings have survived until today. Famously, Czar Peter the Great visited Liepāja incognito at the beginning of the 18th century. He spent a night in the ‘Hoyer’ inn which was built in the 17th century. The house is preserved though not in its original state, but with later additions (most notably the second storey). The same is the case for the building opposite the ‘Hoyer’ inn which according to Maruta Eistere, museum educator of Liepāja Museum, hosted King Charles XII of Sweden for one night when he stayed in Liepāja in 1699. Several other residential buildings were visited during the survey which dated to the 17th and the 18th centuries.

A specific feature of the architectural heritage in Liepāja are several buildings related to trade and the harbour. Among those are three storage buildings from the 17th century (Alttoa 1992, 371). While these buildings are listed as protected monuments, at least one of them showcases building interventions intended to adapt them to modern uses, such as for gastronomic businesses. One of the storage buildings that stands isolated from the other two is also placed immediately adjacent to a parking space and supermarket, limiting the authenticity of its environment. Notably, the former customs building – originally consisting of two slim buildings standing side by side (built in 1772) – has survived in its position along the southern embankment of the channel.

Sabile / Zabeln

From the 9th to the 13th century, Sabile (57° 2' 52.544" N 22° 34' 5.419" E) was the location of a Couronian castle. The area fell under the authority of the Teutonic Order, which constructed a Teutonic Order castle about 1282. An early settlement in the vicinity of the castle formed in the 15th century, but declined and disappeared by the second half of the 16th century. In the 17th century, a new hamlet was established in its place. Already in the 16th century, the slopes of the nearby hills were used to grow wine. During the reign of Duke Jacob Kettler, there were also a linen weaving factory, a lime kiln, a tar burner and several mills which were, however, destroyed during the Swedish-Polish War. In terms of the judicial structure, Sabile was grouped with other districts under the control of the supreme district of Tukums.

From the original Teutonic Order castle, only archaeological remains have survived. Aside from the castle, the Lutheran church testifies to the period of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia. It was constructed in the 17th century and renovated as well as altered in the 19th century. The church is accompanied by a small chapel. The present streetscape of Sabile is dominated by architecture of the 19th and partially the 20th centuries.

Saldus / Frauenburg

Saldus (56° 39' 55.087" N 22° 29' 31.808" E) was founded near a former Couronian castle (9th to 13th centuries). In 1253, the hamlet was placed under authority of the Teutonic Order. The Order erected a castle in the 14th century which was linked to the Commandery (ger. Komturei) in Kuldīga (Pirang 1926, 35, 63). This administrative structure remained in place throughout the period of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia, when Saldus became the seat of a captain who in turn was placed under the supreme captain of Kuldīga. During the reign of Duke Jacob Kettler, a weaving factory, a tannery and an iron foundry were established in Saldus. These industries did not survive the Swedish-Polish War, however.

Little urban heritage has remained in Saldus from the times of the duchy. In terms of individual buildings, the Lutheran church is an important testimony to that period as it was built in 1640. Like most churches of that time, it was renovated in the 19th century and subsequently presents a number of stylistic changes. The urban structure, particularly the street network was partially altered, most notably the block in the east of the city centre, containing several glass-steel buildings and a petrol station. The remainder of the more authentic streetscape west of the city centre presents largely 19th century buildings, with a number of houses from the 20th century and potentially individual buildings from the 18th century. The castle of Saldus was ruined by Swedish troops during the Nordic War and has not survived (Pirang 1926, 63).

Sēlpils / Selburg

Sēlpils (56° 31' 40.854" N 25° 36' 47.25" E) was a bailiwick during the times of the Teutonic Order, which had its seat in the Teutonic Order castle (built in 1373) of the same name. Initially, Gotthard Kettler had considered selecting Vecsēlpils as his secondary residence in addition to Kuldīga. However, the duke eventually chose Jelgava instead. Even before 1600, a settlement with a school and a church had developed near the castle. The bailiwick became one of the four seats of the supreme captains in the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia, after the Formula Regiminis had been adopted in 1617. With Vecsēlpils at its centre, the supreme district stretched along the left bank of the Daugava.

In 1704, during the Nordic War, the Order castle was destroyed by Saxon troops and the adjacent settlement was completely de-populated. Today, Vecsēlpils can only be perceived in the form of archaeological remains. The only exception to this is the former Lutheran church which has survived albeit in a ruinous state.

Skrunda / Schrunden

Skrunda (56° 40' 28.322" N 22° 0' 17.896" E) lies on the left bank of the Venta. As such, it became part of the land under the authority of the Teutonic Order in 1253. As happened in many other places, the Order erected a castle in 1368 to fortify and control the area. However, the castle has not been preserved as it was destroyed during the Nordic War at the beginning of the 18th century. The early industrial developments under Duke Jacob Kettler also had an impact on Skrunda, where a powder mill, facilities for the manufacture of rifles, canons and nails were built. All of these installations were destroyed during the Nordic War as well. In 1704, Skrunda was temporarily the residence of the Dowager Duchess. Administratively, the town hamlet was the seat of a captain who was subordinated to the supreme captain of Kuldīga.

Talsi / Talsen

Talsi (57° 14' 52.948" N 22° 35' 14.59" E) was formed at the location of a former Couronian castle. When this area was placed under control of the Teutonic Order in 1253, the order built a castle on the opposite hill in the 13th century. The first records of a settlement date to 1462 and 1503. Similarly to Kandava, Talsi remained a hamlet during the times of the duchy and only became a town in the late 19th century. When Tukums was categorised as a supreme district in 1653, Talsi was placed under its judicial control as one of its subordinated districts.

Talsi still features a dense and authentic urban structure, large parts of which are placed under monumental protection. However, few buildings from the period of the duchy have survived. Most of these buildings date to the 18th century. Among this group is the Lutheran church which was constructed in the 18th century, though largely remodelled in the 19th century. In its interior, two epitaphs remain from the 18th century. Furthermore, there are also two synagogue buildings near the church which originate from the 18th century. Unfortunately, both were altered in the 19th and 20th centuries so that their exterior barely allows their recognition.

Add Your Heading Text Here

Tukums / Tuckum

Only the Couronian castle mound testifies to the history of Tukums (56° 58' 10.79" N 23° 9' 11.484" E) before the area became part of the Livonian dominion in 1253. The Livonian Order constructed a castle at the end of the 13th century in order to control the so-called Hellweg, the trading route from Riga to Königsberg (Kaliningrad), which passed through the settlement. During the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia, Tukums became a seat of one of the four supreme captains. The following districts were subordinated to Tukums: Nienburg, Autz, Kandava, Sabile and Talsi. Duke Jacob Kettler had a copper smelter built near Tukums, the location of which is known, but today occupied by a small-scale industrial facility. Throughout the period of the duchy, Tukums did not receive town rights. These were only awarded in 1798, after the duchy had been integrated into the Russian Empire.

Of the former Teutonic Order castle, only two elements have remained: one of the castle towers and a small part of the wall which are located south of the market square. While the city centre is placed under monument protection, the majority of the preserved built fabric represents the architecture of the 19th century, with individual building stock from the 18th and 20th century. The oldest building in the city centre is the Lutheran church, which was built in the 17th century and renovated in the 19th century. One of the oldest residential houses is located opposite the market square. It was built in the 18th century and was inhabited by the local pharmacist who had immigrated from Prussia.

Valdemārpils / Sassmacken

The town of Valdemārpils (57° 22' 8.598" N 22° 35' 28.025" E) originated from a fishermen’s village which had developed on the grounds of the Manor of Sasmaka (ger. Sassmacken). The earliest known record about the village dates to the year 1582. Until the 17th century, the hamlet had grown into a village, which only received city rights in the late 19th century, after the duchy had ceased to exist.

With regard to architectural heritage, the town still features a Lutheran church which was constructed in 1646 and is placed under monumental protection. In addition, the former synagogue dating to the 18th century is also preserved. The overall streetscape displays a style predominantly from the 19th century interrupted by 20th century buildings.

Ventspils / Windau

The earliest fortifications which developed into the Teutonic Order’s castle in Ventspils (57° 23' 37.399" N 21° 33' 52.945" E) are likely to have existed since 1263 (Zarāns 2006, 70). The upper storeys were added from the 15th century onwards. During the time of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia, the castle was used for a garrison for which the building had to be adapted. Near the castle, a settlement existed since the 13th century, which grew and was awarded city rights in 1378. In 1440, the merchants of the town started participating in the activities of the Hanseatic League. In an interview during a site visit in the course of the preparation of the Comparative Analysis, Dr. hist. Armands Vijups, deputy director and leading researcher of Ventspils museum, mentioned that, in the 17th century, the former town of Ventspils had to be abandoned due to sand dunes wandering from the west to the east. During the period of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia, specifically from 1666 to 1795, Ventspils was the seat of a captain who was subordinated to the supreme captain of Kuldīga. As one of the most important sea ports of the Duchy of Courland, Ventspils was of strategic significance not only to the duchy, but also to the major powers interested in taking over its territory. As a result, the town was conquered and plundered both by Sweden and Poland in 1658/59, and then again by Sweden during the Nordic War in 1701. Like all Courland towns, Ventspils also suffered during the pestilence outbreak in 1710.

The importance of Ventspils rests in its harbour, which remains ice-free for almost the entire year. As it is also located on the estuary of the Venta, Ventspils was the long-distance trade harbour for the town of Kuldīga which in turn was an important transfer point for goods from land to sea transport. During the reign of Duke Jacob Kettler, Ventspils witnessed a time of growth and prosperity, with a sawmill and a shipyard installed. Subsequently, 44 warships and 75 merchant ships were built in the town, some of which were sold to France and England (Berkis 1969, 64). Ventspils was also the harbour from which the duchy operated its sea trade with the powers in Western Europe and their colonies, as well as the over-sea colonies of the duchy itself, i.e. in Tobago and Gambia. However, in the course of the 18th century, the harbour deteriorated and trading operations declined.

Today, Ventspils is one of the last remaining towns where a complete, though altered Teutonic Order castle has survived. The oldest town building in Ventspils dates to the 17th century and is located on the market square. During a visit to Ventspils, the survey team was guided to a number of other residential buildings which predominantly date to the 18th century and still retain valuable architectural details from that time. Similarly to Liepāja, Ventspils was a harbour town which required specific storage facilities for trade. Unfortunately, only two storage buildings have survived. The older wooden building might date to the 18th century, but was massively altered in order to adapt it to modern use as a leisure facility. The second storage building can be found on the promenade and is a brick building which originates from the 19th century. None of the historic churches appears to have been preserved. While the construction of the Lutheran Church of Saint Nicholas was begun in the 18th century, it was only concluded in the 19th century, as Dr. hist. Armands Vijups confirmed.

In the late 17th century, Swedish spies surveyed the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia with the intent to produce maps which could inform later military interventions in the region. While the map of Ventspils did not provide many details about the town itself, it identified the shipyard and dockyard as two separate locations outside of the town proper. Today, the identification of both locations is still local knowledge, though little material proof has been preserved over the centuries. The site of the historical shipyard is incorporated into the modern harbour area. The dockyard was located further upriver and is marked by a memorial stone.

Intermediate conclusion: Cities of Kurzeme-Zemgale Duchy

The survey of the 17 towns that played a role during the ducal era showed that the ability to physically demonstrate the significance of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia varies significantly between towns.

In Jaunjelgava, Sēlpils and Skrunda, the amount of historical urban fabric dating back to the duchy period ranges from no remains to just a single church. The strength of Aizpute lies in its ability to show both ruins of the Teutonic Order castle and renovations made to them during ducal times, but apart from that little fabric could be identified which carries the proposed Outstanding Universal Value. The relevant remains in Durbe, Grobiņa and Sabile are limited to castle ruins as well as a Lutheran church each. In Tukums, in addition to single elements of the castle and the Lutheran church, one residential building of the 18th century could be identified. Talsi, on the other hand, seemed interesting due to its dense urban structure. Further analysis however showed that apart from a variety of religious buildings, the existing houses were built after 1795. A similar observation could be made in both Jēkabpils and Valdemārpils, where the only buildings representative of the ducal era are a number of religious buildings of different faiths, whereas the earliest residential buildings are from the 19th century. In Saldus, the streetscape also represents the 19th century, with a single church from the era of the Duchy of Courland.

The scarce amount of architectural remains of the 16th to 18th century as well as the lack of authenticity and integrity found at many sites is a result of war-inflicted damages, fire hazards, but also lack of conservational efforts. The consequences of the wars are especially noticeable in Jelgava, with its palace being a reconstruction of the 20th century, lacking also the original interiors. As in other towns, there are a number of religious buildings originating from the 17th century in Jelgava which, however, also had to be restored after the 1944 destruction of the city. Liepāja counts with a variety of residential as well as trade and religious buildings from ducal times, which unfortunately suffer from building interventions and lack authenticity. Similarly, much of the historical fabric existing in Bauska was later altered. What is left are the rich interiors of the Church of the Holy Spirit as well as approximately 15 residential buildings authentic to the ducal era. With regard to its authenticity, Kandava has to be positively noted. Its streetscape is intact and well-preserved. Yet again, the density of architectural remains is limited to a few streets and hence cannot be compared to the extensive testimony to the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia found in Kuldīga. Finally, a number of interesting elements could be found in Ventspils. The city has the only remaining complete Teutonic Order castle in the duchy’s territories as well as residential and storage buildings that represent the trading activities of the duchy. However, similar to other sites described before, the majority of these buildings have been subject to major alterations and hence do not comply with the standards of authenticity needed for UNESCO recognition.

In conclusion, the town survey showed that relevant historical urban fabric can be found throughout Latvia, but nowhere outside of Kuldīga is the authenticity and integrity of the material high enough to tell the overall story of the ducal era.

Additional sites for comparison

Despite this nomination being focused on the urban development of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia, a series of other sites were considered for comparison. In particular, churches, cemeteries, sites of early industrial development, manors, palaces and Couronian villages that are intertwined with the history of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia were analysed.

Churches and cemeteries

Since the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia was formed in 1560, it witnessed the rise of Protestantism. In fact, the political dimension of the inner-Christian conflicts, i.e. between the Catholic Church and the different Protestant movements, can be considered one of the factors shaping the development of the duchy. While Poland-Lithuania, to which the duchy was subordinated as a vassal state, acted as a strong ally of the Catholic Church, the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia was predominantly Lutheran. The predominance of the Lutheran faith was even anchored in the Duchy’s constitutional document, the Pacta Subiectionis, which grants the dukes and their subjects the right to free religious practice in accordance with the Confessio Augustana (Hübner 1993, 31).

In the 16th century, wooden churches existed in many larger settlements and a few towns. Most of these were replaced by masonry churches in the course of the 17th century which can often still be observed today, though these churches were regularly renovated as well as enlarged in the 18th century and particularly in the 19th century. As these building interventions oftentimes widely altered the churches and removed the building layers from the period of the Duchy, few retain heritage values of the 16th to 18th century. The churches and cemeteries that were included in the survey on recommendation of national specialists were worth discussing as potential values of a World Heritage nomination as they partially preserved relevant aspects of Courland craftsmanship. However, churches in a good conservational state proved to exist across the country and authentic typical craftsmanship can be found in ecclesial buildings of Kuldīga. This weakens the necessity for inclusion of additional sites mentioned outside of Kuldīga, as they do not add further value that could not be conveyed by churches in Kuldīga. While elements such as a stone epitaph at Nurmuiža Church, an organ built by Kuldīga citizen Cornelius Rhaneus at Ugāle Church as well as a 16th century confessional at Zlēkas Church are representative of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia, they are not the only candidates to represent authentic attributes of 16th to 18th century interior design, as Kuldīga’s churches, mentioned in Section 2.a, illustrated a similar ability. The churches of Kuldīga, i.e. St Catherine Lutheran Church and Holy Trinity Roman Catholic Church, bear all necessary elements to convey the aspect of the evolution of religious buildings in ducal times as well as the expression of Couronian craftsmanship in their interior design.

Sites of early industrial development

The Duchy of Courland and Semigallia was a highly relevant period for the progress of the predominantly agrarian region, as the dukes – particularly Duke Jacob Kettler – initiated a process of early industrial development which in turn was based on their mercantile policies. The dukes fostered the growth and prosperity of cities and also began to exploit mineral resources. This led to the construction of several early industrial facilities for the processing of the mineral resources, such as copper or the local iron ore, as well as the production of nails, canons, and tools for agriculture. The aspect of industrial development is particularly interesting as it is one of the strongest witnesses to the international exchange the Duchy was involved in. With no tradition of ironmaking existing in the region prior to the 17th century, both knowledge and skill had to be developed through the direct involvement of foreign specialists (Jakovļeva et al. 2019, 102).

Due to the impact the industrial activity of the duchy had on the development of its towns, and given that Kuldīga itself cannot represent this aspect, it is intriguing to add to the nomination a component outside of Kuldīga, testifying to the early industrial development of the Duchy of Courland. Based on the expertise of Mārīte Jakovļeva, who is a renowned specialist on the industrial heritage of the ducal era, only Ēdas and Vecmuiža were relevant in the context of the comparative analysis. Considering Ēdas, despite it being one of the best-conserved industrial sites in Latvia, its state of conservation does not comply with the standards of authenticity and integrity that have to be met in the context of UNESCO World Heritage sites and therefore cannot be further taken into account. In the context of Vecmuiža, the authors of a 2019 archaeological report recommended further investigation in order to fully grasp the interconnection of the tangible evidence and the existing written records. Generally, it has to be noted that the investigation of the early industrial development of the Duchy of Courland is still at the beginning and that a lot more research would be needed in order to decide upon its relevance for UNESCO World Heritage listing.

Manors and palaces

Manors and palaces represent a specific aspect of rural life of the Courland nobility. While a variety of Manors exist across the country, Nurmuiža stands out in terms of authenticity. Currently, however, the focus of the proposed nomination lies on the urban testimony of the duchy, so that no strengthening of the current narrative is to be expected by inclusion of the manor. Rundāle Palace, the most visited heritage site of the country, suffered significant damage in the 20th century, which led to partial reconstruction of the palace.

Couronian villages near Turlava

The Couronian villages were a remarkable exception in the rural sphere of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia. While most Latvian farmers – who provided the majority of the rural workforce and who lived in individual farmsteads – either served on the ducal estates or on the estates of the German nobility, the Couronian villages were inhabited by freemen which were recognised as descendants of the Couronian chiefs, who were exempt from taxes and other imposed liabilities. Already in 1318-33, during the rule of the Teutonic Order, they were awarded significant property rights and other privileges (Lexikon Baltische Ortsnamen II, 171-2) which were also recognised by the dukes of Courland and Semigallia. There were eight villages of this kind that consisted of about 4-5 farmsteads each. The Couronian villages, as well as the church at their centre, give an interesting insight into the unusual setting of the living space of Latvian freemen descendant from Couronian tribes. The villages Ķoniņciems, Kalējciems and Ziemeļciems each consist of up to three wooden or masonry farmsteads. Unfortunately, the tangible evidence available at the sites lies outside of the time frame of interest for the nomination, as it dates back predominantly to the 19th century. Only Lipaiķi Church originates from ducal times. Its heritage value is however directly linked to the villages surrounding it and loses its significance if looked upon outside of its regional context.

Summarised results of the comparative analysis

The attribute mapping conducted in 2019 reinforced that Kuldīga (Goldingen) holds a rich mixture of architectural attributes, giving testimony to the unique role of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia in international (trade) relations and cultural exchanges from the 16th to 18th century. Despite it being a vassal state of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the duchy succeeded in gaining relative political independence, acting with sovereignty far beyond that of other regional powers, and establishing diplomatic and trade relations with numerous major European states and Russia. Located in the centre of the opposing powers of Sweden, Poland-Lithuania and Russia, it furthermore stood out due to its political neutrality and early liberal policies, acting as buffer, mediator and refuge.