Kuldīga’s grand narrative of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia (summary)

Kuldīga (Goldingen) was first documented in 1242. However, the history of the town most relevant to this nomination commences in the late 16th century with the establishment of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia. The historic centre of Kuldīga is a compelling reminder of the Duchy’s era of growth and trade in the late 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, when the town was known by the name Goldingen. The Duchy of Courland and Semigallia was an autonomous vassal state under the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, which stretched from the Baltic Sea Coast in a triangular shape around 500km eastwards to the Daugava River, initially bordering the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Polish Livonia, the Kingdom of Sweden and later the Russian Empire. The dukes of Courland and Semigallia governed this significant part of the Baltics between 1561 and 1795 and left their legacy in the wider geopolitical region.

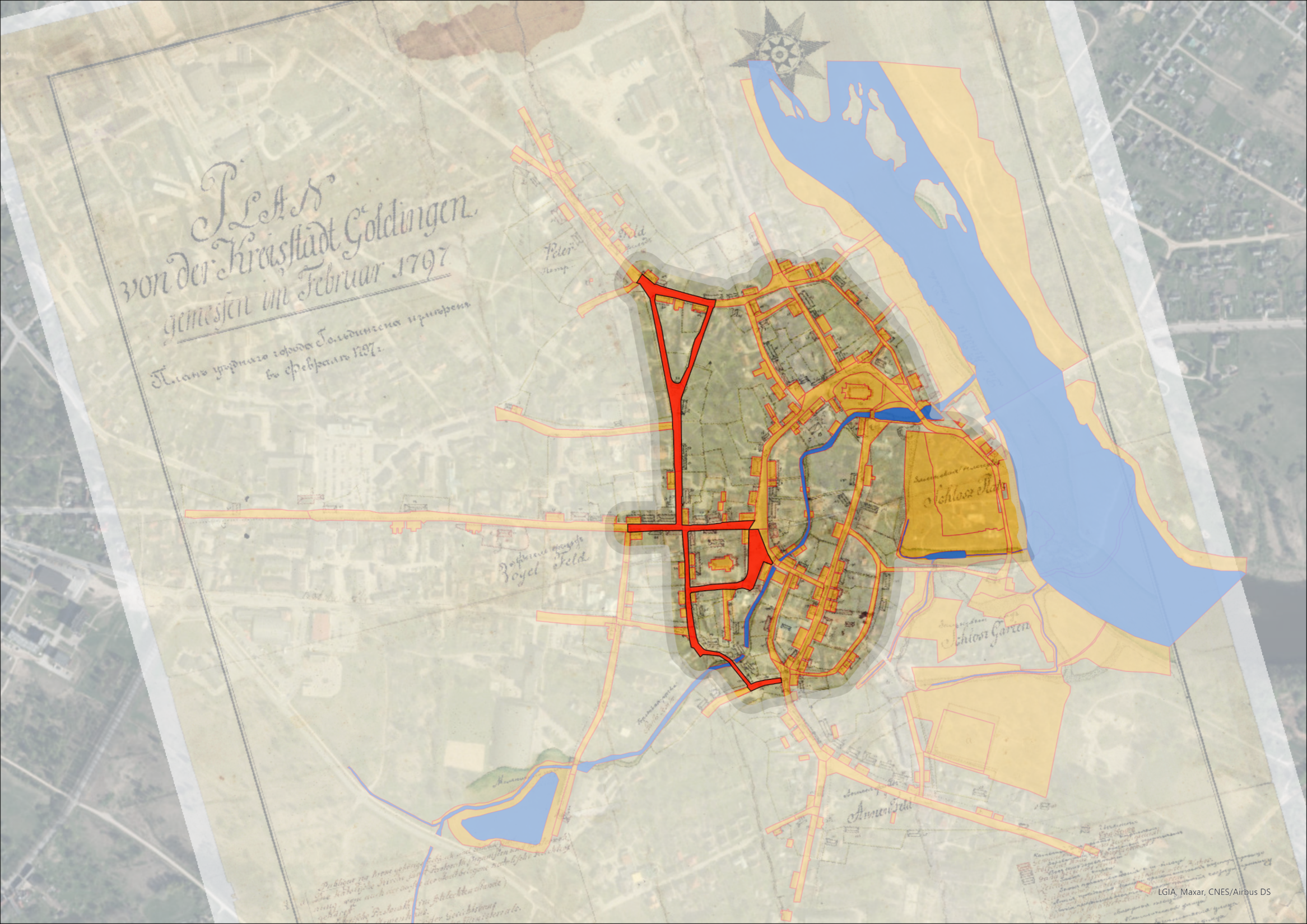

Kuldīga was the primary residence and administrative centre of Courland’s first ruler Gotthart Kettler after the establishment of the Duchy in 1561. During the co-regency of Gotthart Kettler’s heirs, Kuldīga continued to be the ducal residence and administrative centre of Duke Wilhelm Kettler, who had been given power over Courland in 1596 and ruled until 1616. Kuldīga maintained an important role in the administration of the Duchy during its entire existence and continued to grow as a result. In a 1613 census, Kuldīga was documented to have 175 buildings of tax-payers; 149 buildings were indicated on the oldest existing town map, which was created in 1797. The decrease of buildings can be attributed to a series of fires and floods, which were common occurrences at the time, as well as deterioration following the many vacancies based on the decrease of population numbers after the Great Plague.

The proposed Outstanding Universal Value of Kuldīga is derived from its ability to represent the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia which, despite its small size and problematic position among the larger European powers Poland-Lithuania, Sweden and Russia, developed into a maritime power in the 17th century under the rule of Duke Jacob and established an international trade network that spanned from Europe to the African west coast and the Americas. The Duchy of Courland and Semigallia and with it Kuldīga flourished when it increasingly engaged in international trade and communication. For the purposes of trade activities, the small political entity constructed a fleet of its own with the expertise and technologies of international specialists who came to Courland and often settled in the region, bringing with them the building traditions of their home countries. The duchy had trading contracts and diplomatic relations with the dominant European powers, such as France, England and Russia. At this time, various merchants of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia personally travelled to destinations such as Germany, the Netherlands, France and Spain by ship to trade a diverse range of local goods (Scheffler 1940, 28). In addition to merchants from Kuldīga travelling within the Baltics and beyond, foreign merchants also came to Kuldīga, including from Russia during the Great Nordic War at the beginning of the 18th century (Scheffler 1940, 32). Travelling merchants were common visitors to the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia, and they even had their personal seating area in St. Catherine’s Church in Kuldīga (Scheffler 1940, 28).

While many of the international visitors left again after completing their business, others stayed and settled in the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia. In Kuldīga alone, people from a minimum of nine different countries are documented to have settled in the town during the ducal era (see Scheffler 1940). While Germans, especially from northern regions of Germany, always made up a big share of citizens in Kuldīga, the variety of cultural backgrounds broadened along with the growing international relations encouraged by the dukes. In the 17th century, new citizens were registered from Austria, Denmark, France, the Netherlands, Scotland, Sweden and Switzerland. In the 18th century, single cases of settlers were additionally registered from Italy as well as Bohemia (Scheffler 1940, 53). In addition to migration from the European continent as well as the Baltic neighbours, an increase also has to be noted for internal migration, with growing numbers of Couronians settling in Kuldīga (ibid). Migration patterns, especially during the 17th and 18th centuries, illustrate two major developments of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia. Firstly, continuing German immigration along with additional immigration from other European states testifies to the growing importance of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia, which was considered a place worthy of settling in. Secondly, the increasing internal migration from the territory of the Duchy bears witness to the growing importance of Kuldīga as an urban centre of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia despite it not being a sea port.

The growing importance of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia, as well as of the town of Kuldīga, as trading hubs of the 17th and 18th centuries is further highlighted by the records of the occupations of newly arriving citizens. Records in this regard are available for the complete duration of the ducal era. It is striking that whereas only one merchant was registered to have settled in Kuldīga between 1569 and 1599, which is less than 1% of all new residents, this situation changed dramatically over the following centuries. In accordance with the general increase of trading activities of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia, from 1600 until 1649, 10% of all newly registered citizens in Kuldīga were merchants. In the second half of the 17th century, almost 30% of new citizens were merchants, which represents a high-point of trade-related migration and reinforces that the period under Duke Jacob (1642-1682) was in fact the most prosperous economically. In the following century, the numbers were lower than in the high times at the end of the 17th century, but merchants continued to make up around one fifth of all new citizens, representing the largest occupational group and showing the lasting impact the growing trade has had on the organization of society (Scheffler 1940, 26).

In Kuldīga, local and foreign craftsmen jointly developed a new architectural language in the town, which was inspired by international encounters as well as the availability of new materials based on trade relations set up under ducal rule. The historical urban fabric in Kuldīga includes structures of traditional local log architecture as well as largely outside-inspired techniques and styles of brick masonry and timber-framed houses that illustrate the rich exchange of local craftspeople with travelling craftsmen from other Hanse towns and centres around the Baltic Sea as well as Russia.

During the period of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia, Kuldīga was essential for the development of crafts in this region and soon established itself as the centre of Courland craftsmanship . The statutes of the guilds established in Kuldīga were also binding for those craftsmen living and working in other towns of the Duchy. As illustrated by the Kuldīga District Museum through a series of movable objects in 2017, the ancient traditions of craft guilds continued to exist until the 1930s (ibid).

The legacy of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia is further expressed through the variety of intangible heritage expressions that originate from the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia. Broad influences can be found in the culinary heritage of the region as well as in legends, songs and poetry. One of the most prominent legends says that it was during Duke Jacob's reign that potatoes were introduced in Courland. As the duke spent a lot of time in different courts of European rulers, he got acquainted with the plant that is essential for the Latvian cuisine today. It is known that Duke Jacob first ordered the expensive plant for his court from Hamburg, and potatoes later grew in the duke’s gardens. This popular tale of the Latvian people is also celebrated through an art installation organized by the foundation of Imants Ziedonis "Viegli" in cooperation with Kuldīga Municipality on the right bank of the River Venta within the nominated property, where cultural potatoes grow while listening to a special radio station - Potato Field Radio.

Storytelling and the passing down of legends are a significant element of Latvian culture, as the country was among the last countries on the European continent to document legends, stories and songs in writing. Since 2004, Kuldīga has held a storytelling festival where locals and guests enjoy the richness of the oral heritage of the town, including stories from the era of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia. This represents a general strong interest in folk culture amongst the Latvian people. In 2008, the “Baltic Song and Dance Celebrations” were recognised on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. While these celebrations honour the heritage of folk songs and dances, they are closely intertwined with another aspect of Latvian culture, the traditional costumes that are worn at concerts and performances. Every town and village has its own variation of the costume that is part of local identity. The costume worn in Kuldīga includes a particular element that evolved during the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia and which represents the increasing wealth of the small state. In addition to the traditionally woven fabric, women wear large jewellery that represents their status. While this jewellery is not unique to Kuldīga, the town is the only place where the jewellery is made from silver instead of bronze, as this was a special craft skill of Kuldīga craftsmen. This costume, and the knowledge surrounding its origin and fabrication, is a significant element of popular celebrations today, including not only the aforementioned song and dance celebrations, but also more private occasions such as midsummer night or weddings.

Visbeidzot jāpiebilst, ka dažas vispopulārākās Kuldīgas leģendas ir tieši saistītas ar nominētās mantojuma vietas materiālo mantojumu. Viena no visslavenākajām leģendām ir radusi taustāmu izpausmi ēkā Baznīcas ielā 17. Tiek uzskatīts, ka 1702. gadā pie pilsētas birģermeistara viesojās un viņa mājā nakšņoja Zviedrijas karalis Kārlis XII (Dirveiks et al. 2013, 304). Šīs leģendas vēstījumu vēl uzsver šajā ēkā patrepē iebūvēta lāde, kas, kā apgalvots, esot piederējusi Zviedrijas karalim (Dirveiks et al. 2013, 306). Pētnieki noraida šīs leģendas patiesumu, taču šis nostāsts ir populārs vietējo iedzīvotāju vidū un ilustrē to, kā hercogistes ziedu laiki, kad šeit ciemojās augstu stāvoši ārzemju viesi, tiek reproducēti vietējās leģendās un nostāstos. Cita ēka, kura joprojām šodien ir pazīstama ar savu hercogistes laika funkciju, ir unikālā daļēji no koka būvētā ēka Baznīcas ielā 10, kas līdz pat šai dienai bieži tiek saukta par “Hercoga aptieku” (Dirveiks et al. 2013, 304).

In conclusion, Kuldīga comprehensively illustrates the complete narrative of the expansion of urban spaces in the context of 16th to 18th century growth and offers tangible evidence of the unique integration of all aspects of urban and societal development within an impressively compact, largely uninterrupted area. It provides vivid testimony of the duchy’s interaction with relevant contemporary political powers and tangibly manifests the traditions of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia. Kuldīga functions as a key carrier of the legacy of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia, as it successfully preserved a meaningful stage of societal development that articulates in the architectural language of the town as well as in the craft skills performed until today. As a consequence of the many wars that were fought on Latvian territory since the 18th century – during its existence, the Duchy of Courland suffered 81 years of war with neighbouring powers and 110 years of famine (Jākobsone 2013, 32) –, no other place can compare to the volume of attributes of Outstanding Universal Value found in this property.

Detailed chronological accounts of Kuldīga’s history

History preceding the period relevant for the Outstanding Universal Value

The earliest known settlement which can be linked to modern Kuldīga was located about three kilometres downstream from the Old Town, at a place called Veckuldīga (“Old Kuldīga”) Castle Mound and dates to as early as the second half of the late Iron Age (9th –12th centuries) (Asaris, Lūsēns. 2013, 139). During this time, the region south and west of the Daugava River was inhabited by several tribes that centuries later became the foundation of the Latvian nation: the Curonians, the Semigallians, and the Selonians (Berkis 1969, 2).

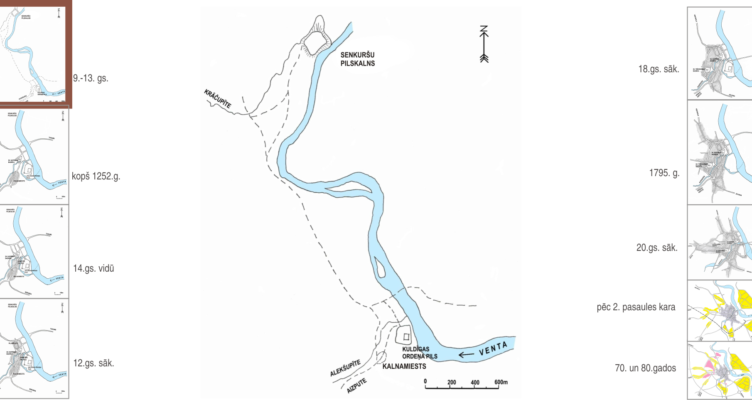

Localisation of the castle mound of ancient curonians in relation to the localisation of the Kuldīga castle. Schematic representation by Jana Jākobsone, Aldis Orniņš, 2012.

Schematic representation by Jana Jākobsone, Aldis Orniņš, 2012. In accordance with the general European situation, this period of history of the Baltics was dominated by the eastward expansion of the Christian faith. After initial peaceful attempts of Christianisation since the 1180s had proven unsuccessful, the Catholic Church decided to pursue its aim by military means (Sarnowsky 2012, 32-33). In 1202, Pope Innocent III confirmed the legitimacy of the Order Frates Milicie Christi de Livonia, better known as the Order of the Sword Brothers, which had the task to support the bishop of Livonia in the conquest of the Baltic region. In 1237, after a major defeat in battle the year before, the order was incorporated into the Teutonic Order by decree of Pope Gregor IX (Sarnowsky 2012, 33). Until 1290, the Teutonic Order – in the form of its Livonian branch – managed to conquer the territory occupied today by the modern state of Latvia. However, the Order did not own all of this territory, but divided it with the Livonian bishoprics, the bishopric of Courland and the archbishopric of Riga. This division of Courland and Semigallia shaped the development of many settlements and towns, and also had a lasting impact on the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia.

Territory of Kalnamiests (Mountain Hamlet) – the earliest settled area. Schematic representation by Inta Jansone according to the research “Kuldīga. Pilsētbūvniecība un arhitektūra”, 2020.

Archaeological excavations took place in Kuldīga for two decades, studying the different cultural layers of the time of the Livonian Order as well as the period of the Duchy, facilitating an understanding of the urban development of the town. Radiocarbon dating in the early 2000s showed that the area known as Kalnamiests (Mountain Hamlet) was populated since the early 13th century, which makes it one of the earliest settled areas of modern Kuldīga (Asaris and Lūsēns 2013, 150). The same research further identified pavement surfaces from the 17th century in this area, proving that the medieval hamlet was later integrated in the early settlement of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia (ibid). Kalnamiests lies at the centre of modern Kuldīga. It consists of the three ielas Kalna Iela, Rumbas Iela and Jelgavas Iela and has an iconic shape that distinguishes it from the rest of the town. Still today, these roads give the impression of the small settlement Kuldīga comprised of at the time. The ielas have a particular oval shape that cannot be found elsewhere in the town. The entire territory of Kalnamiests lies on the eastern bank of Alekšupīte river, about 200 metres inland from Ventas Rumba waterfall.

In the course of its mission, in the following 200 years, the Teutonic Order built many castles to fortify strategically important locations and routes, for example, the trade route from Riga to Königsberg (today: Kaliningrad). These castles oftentimes formed the nucleus of settlements, many of which became towns during the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia, including the town of Kuldīga.

The beginnings of Kuldīga, which was called Goldingen at the time, date back to 1242, when the Papal Legate Wilhelm of Modena gave the Livonian Branch of the Teutonic Order permission to build a castle in order to protect Christianity, similar to other locations in the region (Asaris et al. 2013, 17). The location of the castle was chosen due to its strategic position between Livonia and Prussia, which gave the Teutonic Order the necessary control over the opposing political actors of the time (ibid, 11). Its territory comprises the left bank of the Venta River, north-east of Kalnamiests. The castle itself was separated from the settlement by a moat and its territory was further limited by the Alekšupīte in the north and the Venta in the east. For much of the time under the rule of the Livonian Order, Kuldīga retained the urban layout and volume of a medieval settlement. The castle as the official beginning of the town existed next to the settlement.

Territories of the Kalnamiests (1) and castle (2) – the autonomous settled areas. Schematic representation by Inta Jansone according to the research “Kuldīga. Pilsētbūvniecība un arhitektūra”, 2020.

The first mention of Courland on a world map dates to the time of the Teutonic Order. The Monialium Ebstorfensium Mappamundi, a historic world map created by the monk Gervase of Ebstorf in the 13th century, is considered to be the oldest account of the territory of modern Latvia and mentions Riga, Courland and Semigallia (Zālīte, 2020).

Already in the 14th century, the then hamlet of Kuldīga joined the activities of the Hanseatic League and started to engage in international trade. In 1378, ten years after joining the Hanseatic League, Kuldīga first obtained city rights (Jākobsone 2013, 32).

During this time, a series of urban expansions succeeded in different stages, when the area north of the castle territory was developed. In the course of this development, the first elements essential for the functionality of an organized town, such as a market square and a church, evolved (Scheffler 1940, 5). This was the first time that Kuldīga expanded outside of the area surrounded by the two rivers. Alekšupīte no longer constituted the northern limitation of the settlement. Instead, the river was now flowing right through the centre of the town and the first bridges were built. Across from the Alekšupīte, on the opposite bank of the entrance to the castle, the first town square was created in front of St. Catherine’s Lutheran Church, which was built as the first church of Kuldīga. In this context, Baznīcas Iela was constructed, which connected from the town square past the church south to Kalnamiests, and hence integrated both areas into one administrative system. In the north, five more ielas were added in the area called Pilsmiests (Castle Hamlet). Today, four of these ielas exist, namely Policijas Street, Ventspils Street, Kalku Street and Upes Street.

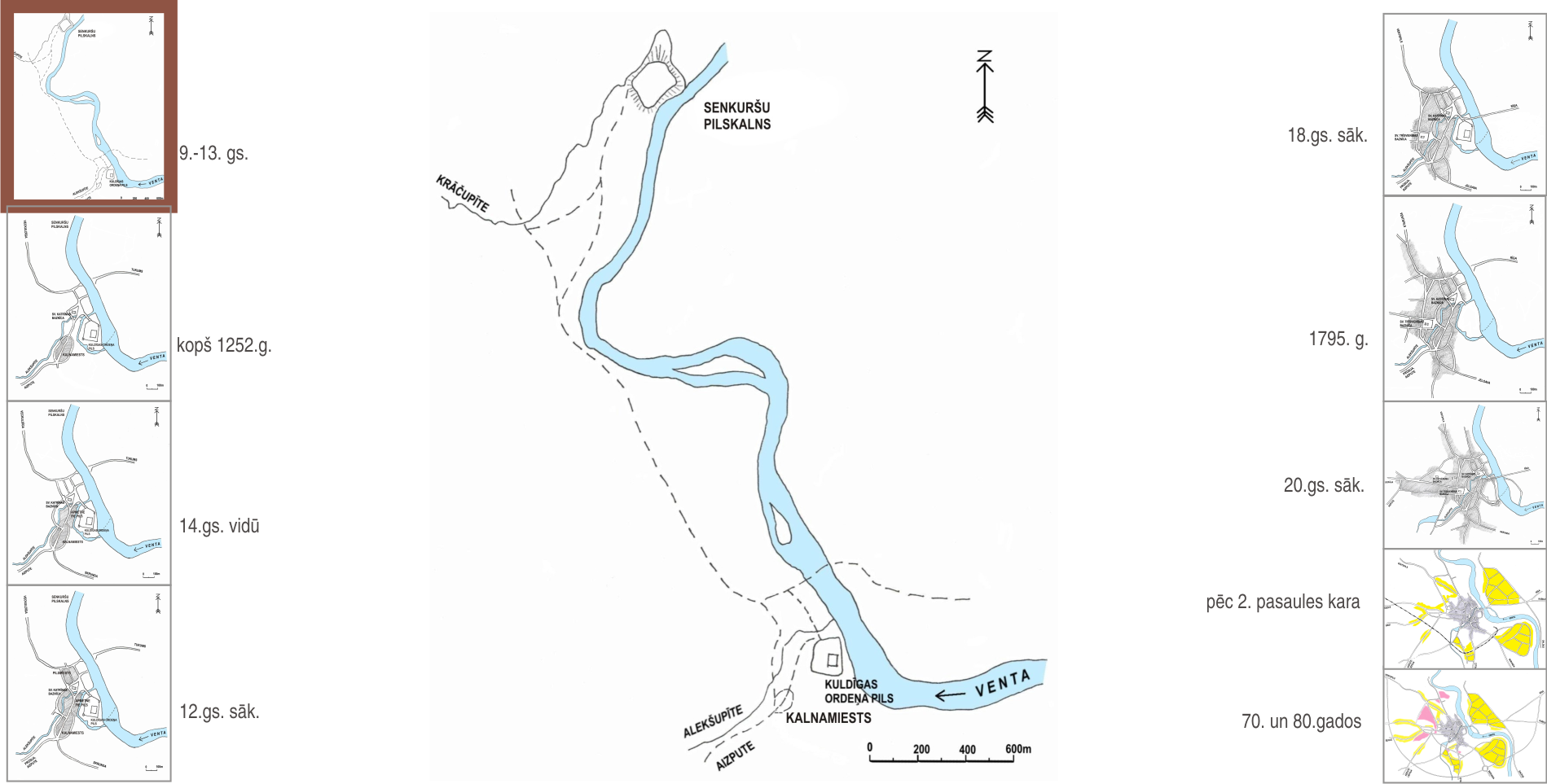

The foundation of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia under Gotthard Kettler

In the history of Europe, the 16th century was a time of great shocks, which also had a direct impact on the territory of present-day Latvia. In the 1520s, the ideas of the Reformation started to spread in Livonia, quickly gaining adherents not only among town dwellers, but also the clergy. At the same time, the struggle for dominance in Livonia between the two main Livonian lords – the Livonian Master of the Teutonic Order and the Archbishop of Riga - intensified. The neighbouring countries – which at this time were undergoing processes of the opposite nature to Livonia, i.e. the centralisation of power and striving towards hegemony in the region – hurried to exploit Livonia’s internal instability. A decisive impetus for changes in the region was the Livonian War (1558–1582), which started with the invasion by the Russian Tsar Ivan IV (the Terrible) into the Bishopric of Dorpat. Since Livonia was unable to offer serious resistance to the troops of the Russian Tsar, its residents sought aid from the closest neighbours, and as a result, in early June 1561, the northern part of Estonia, including Reval (today: Tallinn), accepted the supremacy of King Eric XIV of Sweden. The rest of Livonia came under the lordship of King Sigismund II Augustus of Poland-Lithuania, however, different Livonian territories had different degrees of subjugation to him. In the course of diplomatic negotiations, the Master of the Livonian branch of the Teutonic Order, Gotthard Kettler, managed to acquire the former Order’s lands to the south of the Daugava River – in Courland and Semigallia – transforming him into a worldly prince with the title of a duke. The foundation of the new vassal state – the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia (Ducatus Curlandiae et Semigalliae), shortened as the Duchy of Courland – was based on the so-called Subordination Treaty (Pacta Subiectionis), which was concluded in Vilnius on 28th November 1561.

Territorial division of Livonia in the 16th century. Provided by Mārīte Jakovļeva, 2020.

The Duchy of Courland merits attention by the fact alone that it was the only formation, which under the new conditions, represented local statehood in the territory of former Livonia. In compliance with the Subordination Treaty, Sigismund II Augustus granted the former Order’s properties in Courland and Semigallia as a hereditary fief to Gotthard Kettler. By this treaty, the King guaranteed his new vassal state religious freedom with respect to the Augsburg Confession, confirmed that only the indigenous Germans had the right to occupy administrative positions (the Indigenat) and pledged the preservation of all the existing landlords’ rights and privileges. The duke’s official title was: By the Grace of God the Duke of Courland and Semigallia in Livonia (Von Gottes Gnaden in Liefland zu Curland und Semgallen Herzog). In terms of his rank and regalia, the Duke of Courland stood in the same category as the Duke of Prussia who had become a vassal of Poland-Lithuania in 1525, following the secularisation of the Teutonic Order in Prussia. The Duke of Courland owed to his suzerain the same amount of vassal’s service, i.e. military duties, as the Duke of Prussia. Following the medieval traditions, both the Duke of Prussia and the Duke of Courland had to get their suzerainty reconfirmed by receiving diplomas of ducal investiture at the Royal Court each time a ruler of the duchy or Poland-Lithuania changed. Pacta Subiectionis also stipulated that the inheritance of the Duchy of Courland was allowed only through a direct male line, for which reason in 1566, Gotthard married the Duke Albrecht VII of Mecklenburg’s (1486–1547) daughter Anna (1533–1602), thus laying foundation for the Kettler dynasty. The securing of succession was vitally important for the continued existence of the Duchy as in 1589 the Sejm passed a resolution according to which, upon the end of the Kettler male line, the Duchy could be abolished and its territory annexed to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. In this regard, the Duchy of Courland differed from that of Prussia, the inheritance right of which was extended also to the collateral lines of the House of Hohenzollern that resulted in the merging of the Duchy of Prussia with the Margraviate of Brandenburg in the early 17th century.

The first duke of Courland and Semigallia Gotthard Kettler (1517-1587) and his wife Anna, Princess of Mecklenburg (1533–1602). Epitaph at Jelgava Trinity Church. The epitaph was lost during the World War II. Provided by Mārīte Jakovļeva, 2020.

After the official secularization of the Livonian branch of the Teutonic Order on 5th March 1562, Gotthard Kettler started to develop his power and administrative system. While on the local level the administrative system was largely inherited from the Middle Ages, the highest administrative apparatus had to be built on a completely different foundation since it was no longer a clerical but a secular state. In contrast to the Middle Ages, when the state served religion, the Early Modern Period came with a new approach: religion became one of the political tools of the state, the ruler’s authority was based on “the Grace of God” and he was the Head of the Church. By the Subordination Treaty, the King of Poland had recognised the Lutheran faith as the official religion of the Duchy of Courland and under Gotthard’s supervision the organisation of the evangelical Lutheran Church took place. The Church helped to consolidate the duke’s authority and became a uniting link between the landlords and the duke. Furthermore, under the conditions of the Livonian War, Gotthard tried to keep in his possession the territories granted to him and to ensure the integrity of the duchy. These efforts could succeed only if the duke managed to make the nobility his allies.

The former Order’s vassals formed the leading estate in the duchy – the landlords. The privilege issued by the King of Poland on 28th November 1561 (Privilegium Sigismundi Augusti), as well as the privilege signed by Duke Gotthard on 25th June 1570 (Privilegium Gotthardinum) confirmed full landlords’ jurisdiction over their peasants. Landlords were exempt from taxes, however, they owed the duke military service (the so-called cavalry service – Rossdienst). These privileges in practice turned the fiefs, which had been granted during the Order’s time, into private properties. Thus, approximately two thirds of the duchy’s land came into private hands, while the remaining one third remained at the duke’s direct disposal and formed state property, the income of which was used to sustain the ducal court and civil service.

The most important political, economic and legal matters were reviewed in the diets of the duke and landlords, called landtags, to which, in contrast to the Livonian times, the representatives of the clergy and towns were no longer invited. In the landtag, the towns were represented by the duke and his councillors, to whom the town dwellers submitted their complaints and views on the relevant issues before the respective landtag session. The decisions made at the landtag carried the force of law. Already during the time of Duke Gotthard, foundations were laid for the administrative apparatus of the duchy that centred around the ducal court. In the court, there were concentrated the main officials and institutions related to the state power and administration: the duke’s councillors, chancellery and the highest economic governance body, the treasury, called Rent-Cammer or fürstliche Cammer. At the local level, ducal authority was represented by captains, called Hauptmann, who governed the castle districts that had been formed during the Livonian period, as well as stewards of ducal manors. Towns received from the duke privileges and order or police regulations (Polizey-Ordnung), which were based on the old Lübeck-Visby-Rīga laws.

At this point, Kuldīga consisted of various districts with different functions, such as the castle territory, the medieval Kalnamiests area and the new district developing around St. Catherine’s Lutheran Church, which was the focal point of public functions within the town. The existing districts were combined under a joint legal and economic system.

One of the oldest documents regulating the construction of buildings in Kuldīga dates back to 1577, just 16 years after the establishment of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia. A conserved Police Order illustrates that already in the 16th century official building regulations were read out to the public in Kuldīga once every year (Melluma 2015, 134). With regard to the development of restoration policies, two sections of this document are particularly interesting. Section 13 stated that it was illegal to build “in the market-place, next to and between ielas without permission of the town council” (Melluma 2015, 135). Those who acted in contradiction of this law had to pay a penalty or the illegally built houses were to be demolished. Section 14 furthermore added the aspect of deterioration and building alterations. In order to prevent a problematic state of conservation of the overall town, the town council was granted permission to inspect private buildings and plots whenever considered necessary (Melluma 2015, 135 f.).

Two of the oldest buildings of the town, Saint Catherine’s Lutheran Church as well as Holy Trinity Roman Catholic Church, were renovated multiple times during the period of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia. As they are the major religious buildings of the town, they are important elements of the life of a small town and hence were made a priority of conservation early on.

Territories of the Kalnamiests (1), castle (2), settlement at the castle and Pilsmiests (Castle Hamlet)(3) – autonomous parts of the town before administrative merger. Schematic representation by Inta Jansone according to the research “Kuldīga. Pilsētbūvniecība un arhitektūra”, 2020.

The shared rule of Friedrich and Wilhelm Kettler

Duke Friedrich. A portrait painted by Imants Lancmanis according to samples of the 18th century, at Bauska Castle Museum. Provided by Mārīte Jakovļeva, 2020 Nodrošinājusi Mārīte Jakovļeva, 2020.

Duke Wilhelm. A painting at Rundāle Palace Museum, 17th century. Provided by Mārīte Jakovļeva, 2020. Mārīte Jakovļeva, 2020.

Being aware of the existing external threats and the unstable internal situation, Duke Gotthard wanted to ensure the continued existence of the new state after his death. Therefore, in his will he left the duchy to his two sons. To his eldest son Friedrich (1569–1642) he bequeathed Semigallia with Jelgava in the centre, which was also the residence of the Dowager Duchess Anna, while his youngest son Wilhelm (1574–1640) received Courland with Kuldīga in the centre. However, the most important provision of the will was the prohibition to divide the duchy into two separate parts, the receipt of the fief, i.e. ducal investiture in the Polish-Lithuanian court had to cover the whole of the duchy’s territory at once. In April 1589 in Warsaw, the King of Poland-Lithuania Sigismund III (1566–1632) confirmed the joint rule of the two brothers over the duchy. Friedrich received the investiture diploma personally, while the minor Wilhelm was represented by his councillors. At the same time, the Polish-Lithuanian Sejm adopted the law that, in case the Kettler dynasty came to an end, allowed Courland-Semigallia to be divided into voivodeships and annexed to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania rather than be granted to a new duke as a fief. This provision of Gotthard’s will turned out to be far-sighted, as his eldest son Friedrich died childless and thus the direct line of Kettler rulers in the Duchy of Courland would have ended already in the second generation.

Map of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia (1770): Courland coloured red, Semigallia – yellow. Map from the Latvian State History Archive, fund ID 6828, description ID 2, case ID 208.

At the time of Duke Gotthard’s death, his youngest son Wilhelm was almost 13 years old. He was sent to Rostock to study until he came of age, which in the will was set at 20 years of age, and there he spent four years. During this time, Wilhelm also maintained close contacts with his mother’s relatives and met many representatives of the ruling houses of Europe. During his brother’s absence, the reins of the duchy were in the hands of Friedrich who was helped by a range of councillors and the dowager duchess. Friedrich received his education locally in Courland, but he also made several prolonged trips to Europe. After Wilhelm’s return from abroad, on 23rd May 1595, the two brothers signed a special agreement on the distribution of power, according to which each of them were to have a separate ducal court, economic administration and lower jurisdiction, however the landtags had to be held jointly, thus asserting the duchy’s territorial integrity. Wilhelm settled in Kuldīga, where he established his ducal court. However, Wilhelm’s attempts to free himself from the landlords’ influence in administrative matters and to introduce an absolutist government were met with fierce resistance and as a result open conflict broke out.

Sofia, Princess of Prussia, wife of Duke Wilhelm. Painting by Daniel Rose at the Rundāle Palace (around 1606). Provided by Mārīte Jakovļeva, 2020.

Duchess Elisabeth Magdalene, wife of Duke Friedrich. Golden medallion (1600) in Bode-Museum in Berlin. Provided by Mārīte Jakovļeva, 2020

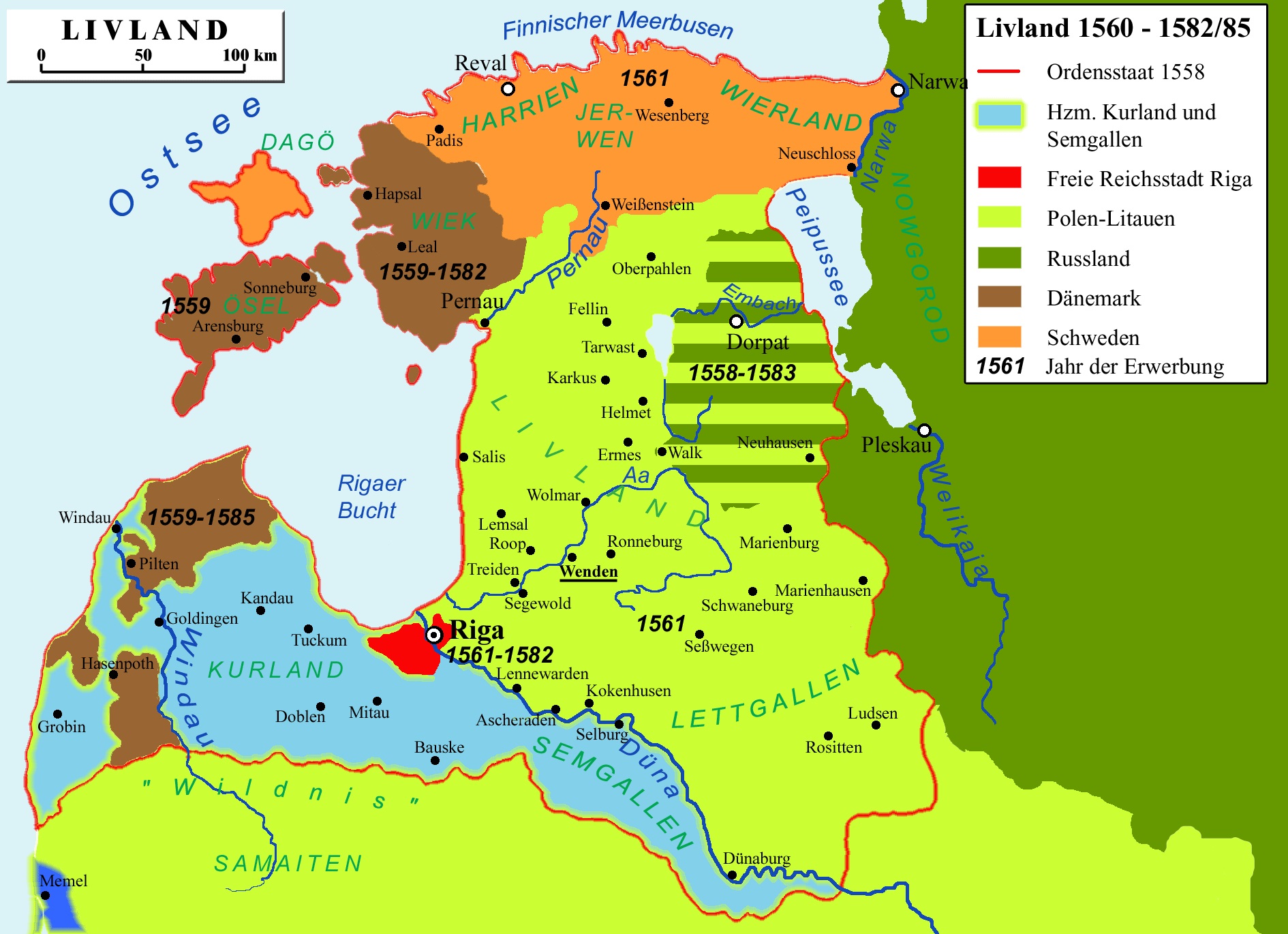

The two dukes continued to make regular trips abroad, acquainting various courts with the new dynasty and broadening their own horizons. In Wolgast, in 1600, Duke Friedrich married the daughter of Duke Ernst Ludwig of Pomerania-Wolgast (1545–1592), Elisabeth Magdalene (1580–1649). Duke Wilhelm in turn married the daughter of Duke Albrecht Friedrich of Prussia (1533–1618), Sofia (1582–1610). Meanwhile, the peaceful life in the duchy was disrupted by the outbreak of the Polish-Swedish War (1600–1629). In the first phase of the war, the two dukes personally fulfilled their vassals’ duties and the arrival of the unit commanded by Friedrich on the battlefield at Kircholm in September 1605 contributed to the victory of the Lithuanian army over numerically much stronger Swedish troops. Duke Wilhelm also joined the troops several times. Yet, it was only the engagement of Poland-Lithuania and Sweden in the developments in Russia (Smuta) and the Danish attack on Sweden in 1611 that saved the duchy from complete devastation. At the same time, the situation in the duchy continued to heat up. The prudent Friedrich tried to reconcile the conflicting parties, but his efforts failed. The turning point in the history of the duchy was the death of the leaders of the landlords’ opposition during their arrest in 1615. The landlords believed that Wilhelm had explicitly given an order to kill them and that Friedrich had been informed, thus they submitted a complaint against the two dukes to the King of Poland Sigismund III. The king deposed the two dukes. As a result, Wilhelm lost his ducal rights and had to go into exile in Pomerania, while Friedrich with great effort managed to justify himself and preserve the entirety of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia under his authority. However, the landlords had gained the upper hand as attested by the constitution of the duchy, called the Formula of Government (Formula Regiminis), which was proclaimed on 18th March 1617. The Formula of Government dictated the political system, limiting the ducal authority in favour of the landlords, and remained in force until the liquidation of the duchy in 1795.Formula Regiminis). ”Valdības formula“ noteica valsts iekārtu, ierobežojot hercoga varu par labu muižniecībai, un palika spēkā līdz pat hercogistes likvidācijai 1795. gadā.

Cover of “the Formula of Government” (Formula Regiminis). Duplicate of the 18th century. Latvian State History Archive, fund ID 5759, description ID 2, case ID 155.

The Formula of Government abolished the institution of ducal councillors and henceforth the government of the duchy consisted of four senior councillors (Oberräte): Landhofmeister, chancellor, Oberburggraf and land marshal. They could be appointed only from among the representatives of the local families listed in a special nobility register, called Adelsmatrikel. The duke was not allowed to make any important political decision without the approval of the Oberräte, especially if the matter concerned the landlords’ rights and privileges. In case of the duke’s absence, minority, illness or death, the board of the senior councillors were to assume the governance of the duchy. Administratively, the duchy was divided into Kuldīga, Tukums, Jelgava and Sēlpils supreme captain’s districts (Oberhauptmannschaften) and these – into the so-called political parishes (politische Kirchspiele). Apart from that, there were also eight captain’s districts (Hauptmannschaften) in the duchy. The captains’ and supreme captains’ positions also were reserved for the representatives of the noble families listed in the Adelsmatrikel, that called themselves ‘the true nobles’ (vera Nobiles) or the knights (Ritterschaft). Duke Wilhelm’s supporters naturally were not admitted into this corporation. Furthermore, ‘the Formula of Government’ stipulated that the landtags of the duchy had to convene at least once in two years. While previously any landlord could take part in the diet, now the participation was reserved only to representatives from among the privileged nobility and each political parish had one vote. The decisions made at the previous landtag sessions lost the force of law. The constitution also demanded the introduction of the Gregorian calendar, i.e. the ‘new style’ in the duchy, starting from 1st January 1618. The adoption of ‘the Formula of Government’ meant the approval of an aristocratic system of government in the duchy, in practice mirroring the processes that took place also in Poland-Lithuania, i.e. the weakening of the king’s central authority and the growth of the magnates’ influence. Regrettably, the Duke of Courland lacked strong backing and opportunities, such as were enjoyed, for example, by the Duchy of Prussia which was eventually annexed to the lands of the Elector of Brandenburg and became the base for the Hohenzollern kingdom. The Duke of Courland likewise did not dare to seek support from among the masses of the local population, which mostly consisted of the Latvians, the bulk of whom were attached to the land as serfs, only relatively few enjoying their personal freedom. The Latvians constituted the economic foundation of the duchy, working in agriculture, fishing, crafts, retail trade, etc., yet they had no political rights.

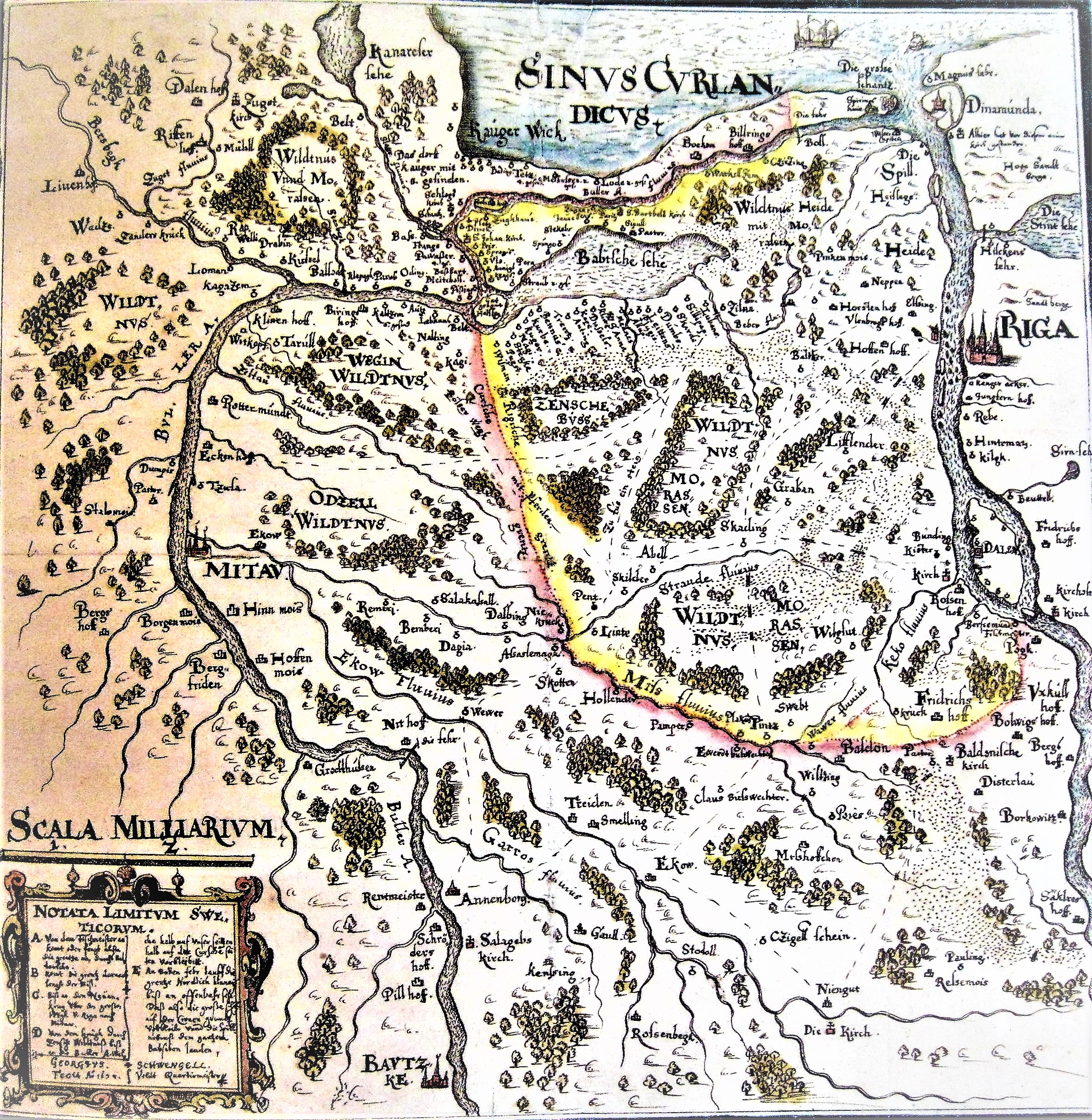

Border of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia and Sweden at Rīga. Map drawn by Georg Schwengeln (1634). Provided by Mārīte Jakovļeva, 2020.

The settlement of the internal conflict did not mean that all threats to the continued existence of the duchy as such were averted. In 1621, warfare resumed in the Baltic. In September, the Swedes took Riga and in October entered the Duchy of Courland and occupied Jelgava Palace. Polish troops arrived in the duchy at the same time. Almost a year later, Duke Friedrich regained his palace, but in the summer and autumn of 1625, the Swedes again occupied part of the duchy. The prolonged war forced Duke Friedrich to seek non-military solutions for the protection of the duchy by trying to secure for it the status of a neutral state. Negotiations for the recognition of the duchy’s neutrality lasted for several years and the two warring parties periodically made promises to abstain from warfare in the territory of the duchy, but these promises were seldom kept. The Courlanders also made efforts to reconcile Poland-Lithuania and Sweden. It was largely thanks to the diplomatic efforts of Courland that at Christmas of 1628 a truce was signed, which in September 1629 was extended by six years and in 1635 by another 26 years. As a result of the war, the duchy acquired a new neighbour – Sweden. In the summer of 1630, the Swedes forced Duke Friedrich to sign a special border treaty, by which the former kept several territories in the lower reaches of the Daugava River which previously had belonged to the duchy.

The reign of Duke Jacob

Duke Jacob. Painting at the Gripsholm Castle in Sweden (1670-ies). Provided by Mārīte Jakovļeva, 2020.

Another problem which threatened the existence of the Duchy of Courland was the succession to the throne. There were no children in the marriage between Duke Friedrich and Elisabeth Magdalena, and after his father was deposed Duke Wilhelm’s only son Jacob (1610–1681) had lost any right to the throne. Thus, for the Kettlers to be able to continue ruling in the Duchy of Courland, Wilhelm’s restitution or at least the recognition of Prince Jacob’s succession rights on the part of Poland-Lithuania had to be achieved. In this matter, Friedrich received support from the majority of the duchy’s landlords who were satisfied with their position and did not wish Courland to be incorporated into the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth after Friedrich’s death or annexed to Sweden, where royal authority was strong. The efforts to win the succession rights for Jacob, who had been named in honour of King James Stuart of England and Scotland (1566–1625), went on for more than 20 years. Only in 1632, after the death of King Sigismund III of Poland, thanks to family contacts and support from Brandenburg-Prussia, Pomerania, Mecklenburg, Saxony, England and even France, as well as the influential Radzivill clan from Poland-Lithuania, the Polish-Lithuanian Sejm declared the restitution of Wilhelm and Jacob’s rights. The new King of Poland Władysław IV (1595–1648), who ascended to the throne in November 1632, accepted it, but only on condition that Wilhelm would never return to Courland.

Since the mother of Wilhelm’s son Jacob, princess Sofia died soon after giving birth to him, at the age of two he was sent by his father to live with his relatives in Germany. Jacob spent his childhood at the Königsberg and Berlin courts and studied for several semesters at Leipzig University. In 1624, Duke Friedrich summoned Jacob to Courland to prepare him for eventually becoming a duke and in 1638 appointed him co-ruler. Before that, Jacob had spent two years on a gentleman’s tour. During this time, he visited his father, who lived in Pomerania until his death, stayed in Holland and France for longer periods as well as travelled to several other European countries. In the 1630s, Duke Friedrich handed Wilhelm’s former dominions over to Jacob, including Kuldīga, which, in spite of all the developments and political changes, still maintained the status of the capital of a part of the Duchy of Courland.

After Friedrich’s death in 1642, Jacob took over as ruler of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia. Ascending to the throne on 29th November 1642, he had to conclude a special reconciliation agreement with the landlords, clarifying a few issues pertaining to the organisation of government. Among other things, it was stipulated the henceforth Jelgava would be the only capital of the duchy. Although Kuldīga lost its capital status, the duke still liked to stay there. On the demand of Poland-Lithuania, Jacob had to build Catholic churches in Kuldīga and Jelgava.

Birži iron manucacture (Grossbuschhofsches Eisenwerk) near nowadays Jēkabpils. Clipping from a 1668 map. Latvian State History Archive, fund ID 673, description ID 1, case ID 979.

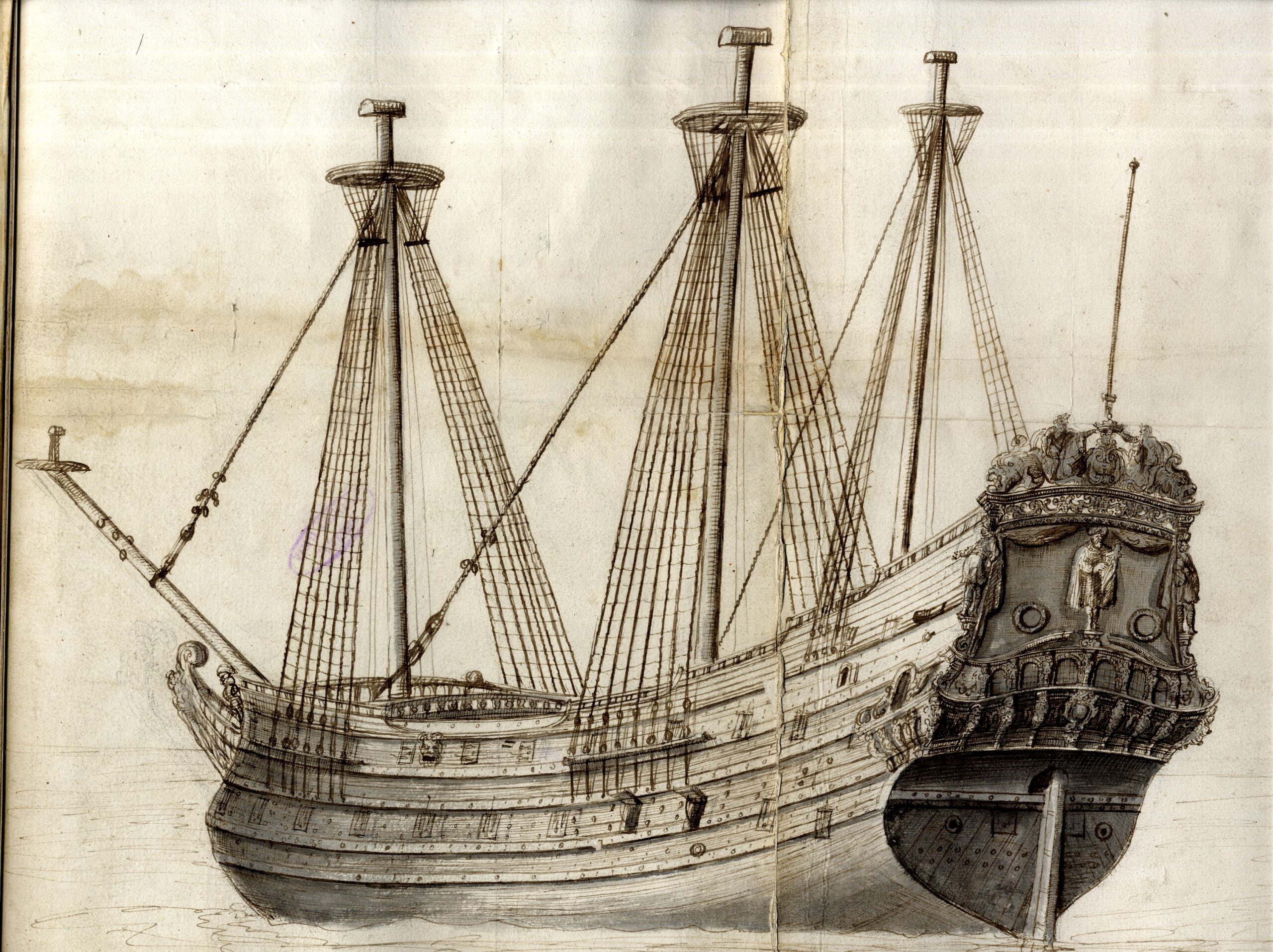

Model according to which frigates were built at Ventspils Shipyard (painting of the first half of the 17th century). Latvian State History Archive, fund ID 554, description ID 1, case ID 850

As he started his rule, Jacob did not wish to engage openly in conflict with the landlords and tried to consolidate the ducal authority by economic means. He increased the export of the products of the ducal manors to Western Europe and tried to channel through Courland a large part of the transit trade that flowed from the east (from Russia and frontier regions of Poland-Lithuania) which until then had been the prerogative of Swedish-governed Riga. At that time the most important routes for trade with Europe were the maritime ones, thus Jacob built a fleet of his own – the biggest fleet among the Baltic countries –, by establishing a shipyard in Ventspils. Following the spirit of the age and the traditions created by his predecessors, he tried to improve manorial efficiency and founded manufactures for various branches of production, including iron manufactures for processing the local bog ore. Jacob recruited experts throughout Europe, thus the duchy saw an influx of representatives of different nations who brought with them new technologies and know-how. Duke Jacob’s efforts in establishing manufactures was a unique phenomenon in the agriculture-oriented region, making him famous far beyond the borders of his state. For example, Jacob advised Russian Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich (1629–1676) on ship-building, metal and glass smelting and trade opportunities in the West Indies. At the same time, the Duchy of Courland became the point of intersection in the transfer of technologies, from where specialists recruited in the west often travelled further eastwards to the lands of Poland-Lithuania and, as already mentioned, Russia. Significantly, in the iron factories built by Tsar Peter I (1672–1725) in the Urals in 1702, the first cast-iron cannons were made in 1702 by master Eric De Pree whom the Tsar had recruited in Courland and whose ancestors had arrived in the duchy in the mid-17th century.

International trade and colonisation

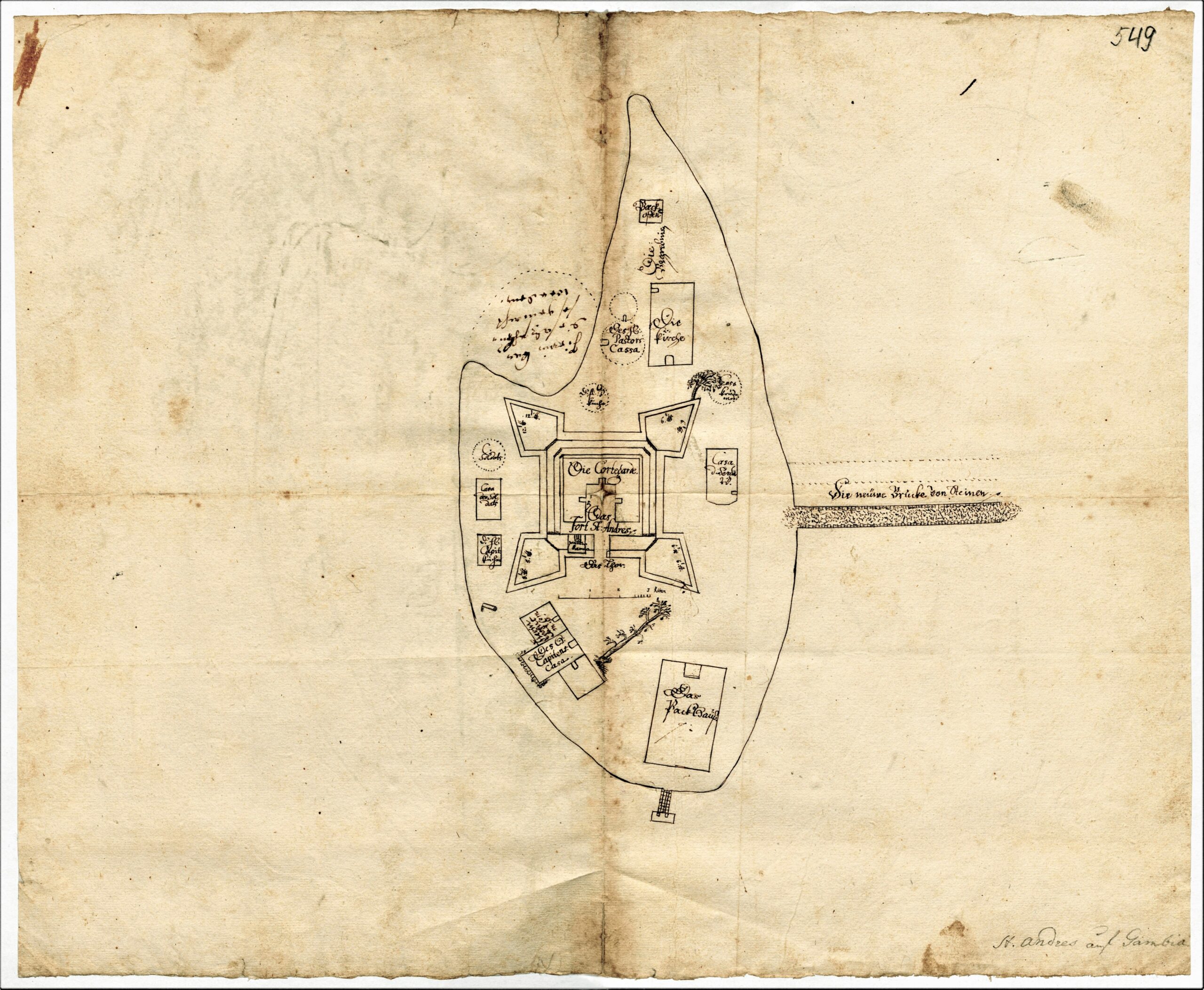

Settlement of Courlanders at St. Andrew’s Island in Gambia (1651). Latvian State History Archive, fund ID 7363, description ID 3, case ID 111.

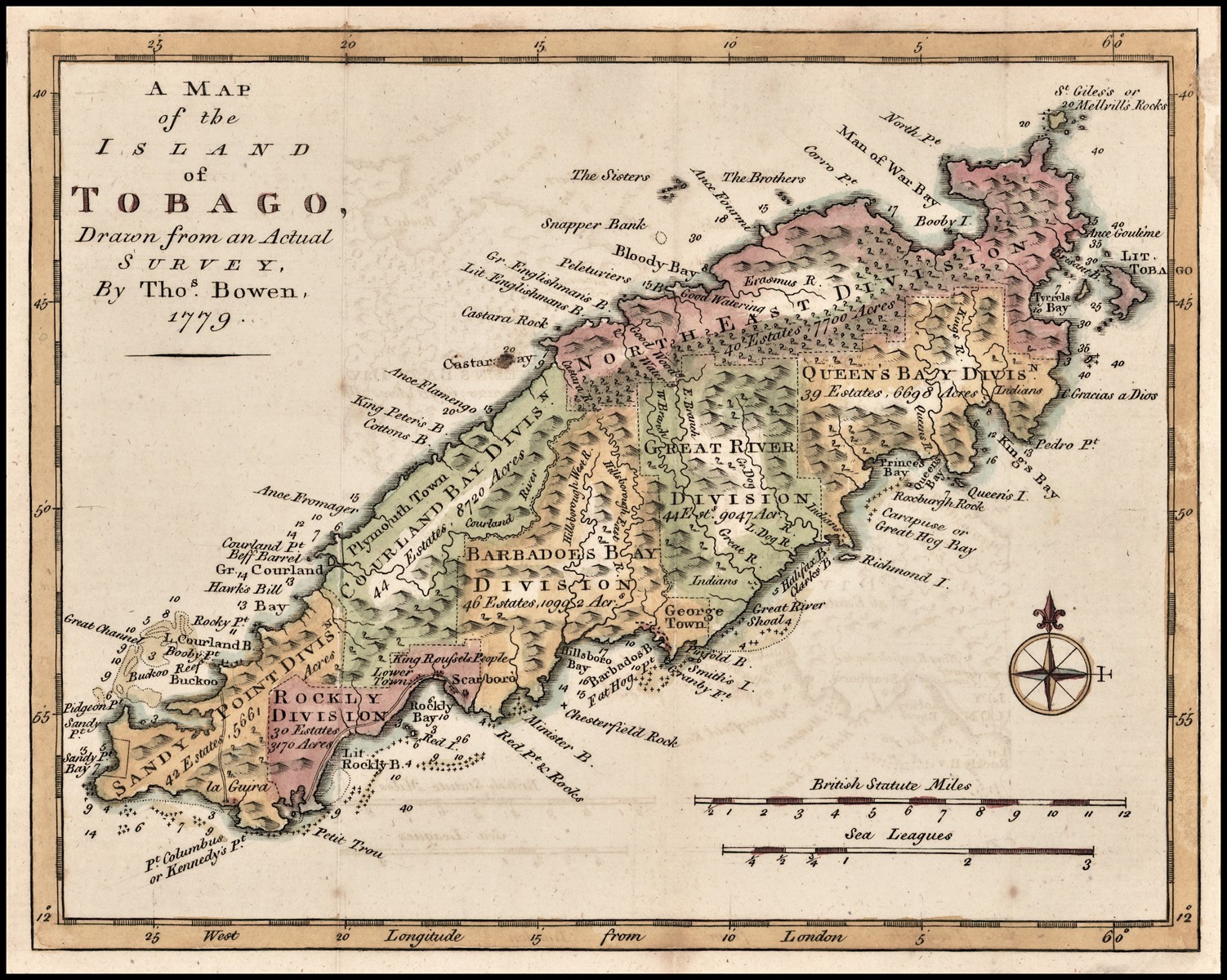

Map of Tobago (1779). Provided by Mārīte Jakovļeva, 2020.

An essential part of a mercantile economy, the most up to date socio-economic doctrine of the day which the duke followed, was the acquisition of colonies in distant continents. Thanks to Jacob’s activities, the name of the small duchy was heard not only all over Europe, but became known also in the coastal territories of Africa and America. In the mid-17th century, Jacob acquired several strong points in the estuary of the Gambia River in Africa (1651) and Tobago in the Caribbean (1654). Although due to another Polish-Swedish War (1655–1660), which also hit the Duchy of Courland hard, Jacob failed to consolidate his authority in his colonies for a protracted period, the Courlanders’ presence can still be felt in Tobago today. Place names seen on the map of Tobago – Fort James, Fort Bennett, Great Courland Bay and Courland River – are direct evidence of the Duke of Courland’s activities. Duke Jacob also dreamed of reaching India and discovering new lands further to the east in Terra Australis. In the 1650s, Jacob, who was a Lutheran but tolerant in religious matters, invited Pope Innocent X (1574–1655) to take part in the implementation of these plans, pledging to hand over ecclesiastic supremacy in the new lands to the Catholic Church. However, the negotiations were cut short by the pope’s death and his successor did not show any interest in the project.

Map of Tobago (New Courland) drawn by Courlanders (1654). Latvian State History Archive, fund ID 7363, description ID 3, case ID 111.

Duke Jacob’s foreign policy was closely associated with his economic and colonial plans. This is shown by his trade and shipping contracts with France and England, mining privileges he acquired in Norway as well as diplomatic relations established between the Duchy of Courland and Russia. After Jacob’s marriage to Luise Charlotte (1617–1676), sister of the Elector of Brandenburg Friedrich Wilhelm (known as ‘the Grand Elector’ 1620–1688), in 1645, the Ducal House of Courland became further integrated into the Hohenzollern dynastic network, which was later attested by the marriage of Jacob and Luise Charlotte’s children to the princes and princesses of Hessen-Kassel, Hessen-Homburg and Brandenburg. It should also be mentioned that Prince Friedrich of Hessen-Kassel (1676–1751), who in 1720 became the King of Sweden, was Duke Jacob’s grandson. In turn, the Elector of Brandenburg took a lively interest in Duke Jacob’s activities, especially in the field of overseas trade, and followed his brother-in-law’s lead in his own colonial policies.

In the 17th century, the increasing economic development of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia led to further urban expansion of the town of Kuldīga and numerous urban elements developed which significantly contribute to the image of the town today. As the previous town square in the Church district had become too small for the growing population, an additional town square was built at the location of today’s Town Hall square, together with the construction of a Town Hall beginning from 1626. Over the next decades, today’s Town Hall Square started to develop in the centre of Kuldīga, with shops opening around it (Jākobsone 2013, 36). The old town centre with the square next to St. Catherine’s Church soon lost its meaning as, in the course of rapid economic growth, the Town Hall square developed into the new centre of Kuldīga where all major roads passed by (Scheffler 1940, 11).

As the religious diversity expanded during this period, a second church district was built west of the Town Hall square for the religious needs of Catholic citizens. The north-western part of the town developed in close connection with the development of the Jewish community. In addition to economic growth, the urban layout of the 17th century hence also reflected the societal changes in Kuldīga, mainly an increase of inhabitants and a wider variety of religious and cultural backgrounds of the people who lived in the town.

At the same time, roads were given increasing importance due to the stronger focus on economic activities. The material excavated beneath the ielas in the course of archaeological research showed that in the 13th and 14th centuries ielas were either covered by waste or paved with logs (Asaris and Lūsēns 2013, 158). With the increase of economic activities introduced by the dukes of Courland, paving of roads became more important. The nobility ensured constant maintenance of the streets so that the postal service, which was an important element of the growing economy responsible for the transportation and delivery of goods, could operate quickly; even quicker than the postal services of the surrounding states (Biedriņš and Jākobsone 2013, 209). By this time, approximately 90% of the iela network of the nominated property had been developed. Remains of the earliest paving’s made of pebbles, pieces of brick or brushwood in the early 17th century were excavated in Liepājas Iela, Baznīcas Iela, Dzirnavu Iela, Rumbas Iela, Kaļķu Iela, Kalna Iela and Policijas Iela (Asaris and Lūsēns 2013, 158).

The expansion of Kuldīga’s urban layout in the 17th century. Schematic representation by Inta Jansone according to the research “Kuldīga. Pilsētbūvniecība un arhitektūra”, 2020.

Cannons of the 17th – 18th century near Kuldīga District Museum at 5 Pils Street. Photo by Kārlis Komarovskis, 2020.

A period of crisis

Duke Jacob’s activities reached their apex in the first half of the 1650s. Regretfully, the successful development of the duchy was cut short by yet another round of military conflicts in the region. Pursuing the policy set by his uncle Duke Friedrich, Jacob strictly preserved the neutrality of the Duchy of Courland which, in view of the growing ambitions of the neighbouring countries, was not an easy task. Under the Polish-Swedish truce signed in Stuhmsdorf in 1635, the Duke of Courland along with the Elector of Brandenburg were appointed ‘peace procurators’ who had to ensure that the 26-year truce became ‘a perpetual peace’. Since Duke Jacob was well aware that without a lasting peace between Poland-Lithuania and Sweden all his efforts would be in vain, in the first two decades of his rule, reconciliation between Poland-Lithuania and Sweden was one of his most important diplomatic goals. Over several years, Duke Jacob organised negotiations between the two parties, involving as mediators also Brandenburg-Prussia, France, Estates-General of France and Venice. Regretfully, the peace congress that convened in Lübeck in 1651 and, with intervals, lasted for two years, ended without result. Soon warfare started within close proximity of the borders of the Duchy of Courland. First, in 1654, war broke out between Poland-Lithuania and Russia; then, in 1655, Sweden engaged in military activities against Poland-Lithuania and a year later also against Russia. Duke Jacob tried to achieve reconciliation between Sweden and Poland-Lithuania as late as 1655, when the Chancellor of Courland Melchior von Foelckersa (also Voelckersamb) tried to persuade the King of Sweden to meet the envoys of the King of Poland for negotiations, first lobbying in Stockholm and then following the former to Danzig (mod. Gdansk). The Chancellor was also assigned with the task of achieving the recognition of Courland’s neutrality by Sweden. It was reported that King Carl X Gustav (1622–1660) said the following about Jacob: “The Duke of Courland is too powerful to be a duke, but not powerful enough to be a king.” The Swedes pledged not to harm the duchy on condition that they were guaranteed provisions during the march of their army and kept this promise until the autumn of 1658. In turn, in the first years of the war, Jacob managed to obtain written confirmation of the duchy’s neutrality from the Tsar of Russia and King of Poland as it was advantageous for them to use the territory of the duchy as a diplomatic channel, through which envoys of different countries travelled in different directions. Not infrequently, the court of the Duke of Courland served as a venue for the envoys to exchange topical information unofficially.

However, respect for Jacob was not an obstacle for the Swedes to invade the duchy in October 1658, capture the duke and his family and holding them captive for more than a year and a half, first in Riga and then in Ivangorod fortress at the Narva River. Although a range of rulers, for example the Electors of Brandenburg-Prussia, Saxony, Mainz and Cologne, Dukes of Braunschweig-Lüneburg and Braunschweig-Kallenberg, Landgrave of Hessen and even the Holy Roman Emperor, called for the duke’s release, the King of Sweden ignored all pleas. The defence capacities of the Duchy of Courland itself were weak as, fearing the growth of the ducal power, the landlords had been against the reform of the military system, which remained based on the vassals’ service. Thus, the Swedes quickly captured the duchy’s territory but were soon countered by the Courlanders’ units, the troops of Poland-Lithuania and the Elector of Brandenburg. The flames of war wreaked huge damage, the majority of the ducal enterprises were devastated and his palaces were plundered.

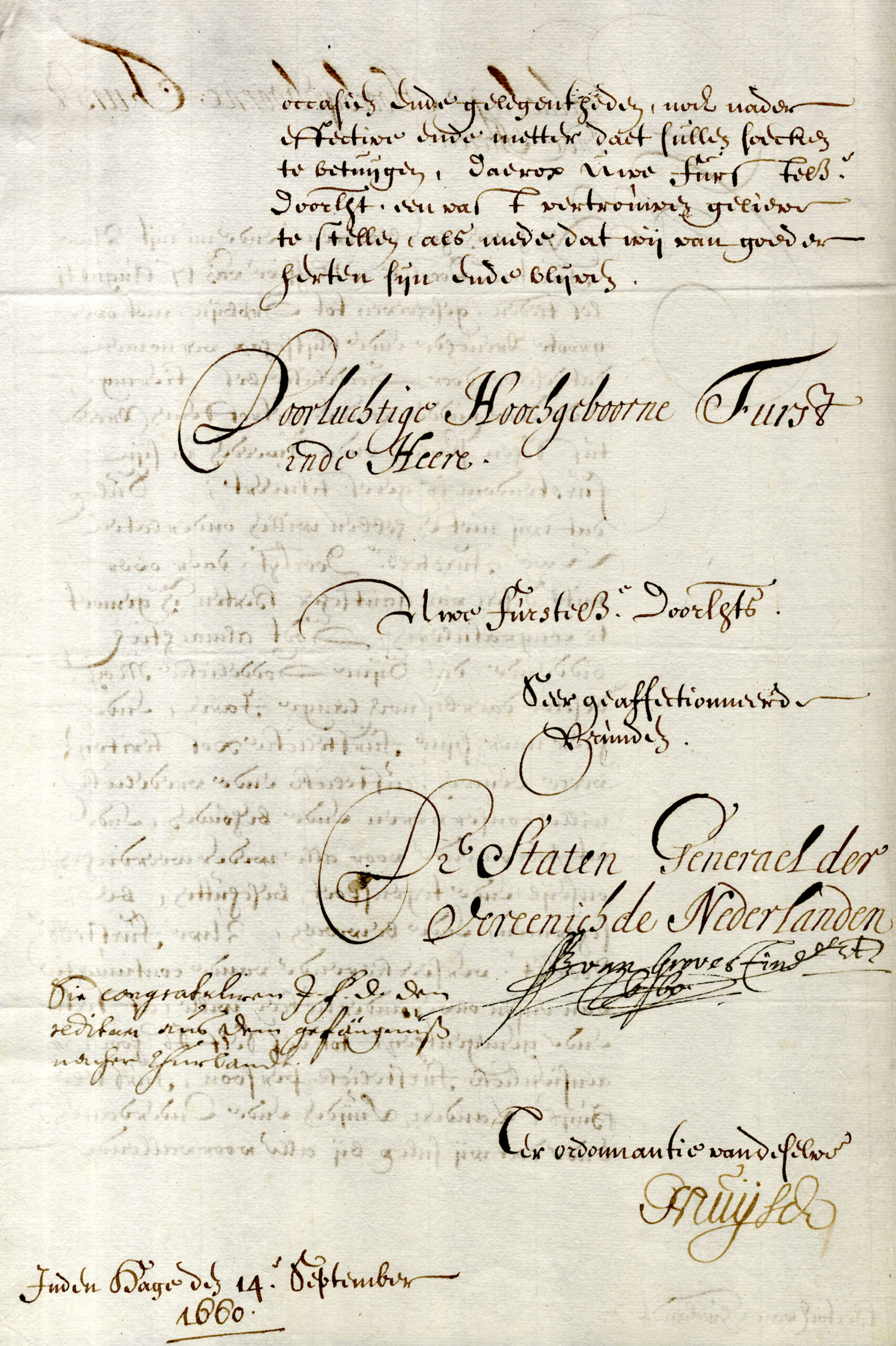

Greetings of the State General of the Netherlands to Duke Jacob with his return from captivity. In Hague, September 14, 1660. Last page. Latvian State History Archive, fund ID 5759, description ID 2, case ID 1324, page 2.

None of the warring parties managed to get a clear upper hand in the war. During the peace talks that took place in the winter and spring of 1660, the Swedes demanded Courland, and among the Polish-Lithuanian party there also were voices that wished to see the duchy incorporated into Lithuania. It was only thanks to the support of France and Brandenburg-Prussia that the Courlandish delegation managed to achieve the restitution of Duke Jacob. After the signing of the Oliva peace treaty between Poland-Lithuania and Sweden, Jacob was allowed to leave Ivangorod and return to Courland, where he was ceremoniously welcomed in July 1660. Immediately after his release from captivity the duke started to rebuild the devastated economy. This required great effort and spending; nevertheless, it proved impossible to reach the pre-war level. Both captivity and advanced years took their toll on Jacob; furthermore, the prices of agricultural products were in decline in Europe from the 1660s, and hence, trade no longer brought the revenue it used to. The duke also exerted great effort to regain his colonies, which had been lost during the war. In 1664, Jacob received from the King of England formal confirmation of his right to Tobago, in return handing over his colonies in Gambia to the English. Yet, in reality, Tobago was in Dutch hands and it was only in 1679 that the Courlanders managed to restore their colony on the island. However, nothing could stop Jacob’s ambitious plans. Until the end of his life he cherished a dream about Trinidad, which he wanted to receive as compensation for his ships and goods captured by Spanish buccaneers, and he tried to regain his right to the Gambian properties from the English. Moreover, in 1677, when rumours about a new campaign by the Russian Tsar against the Swedes were in the air, Jacob proposed Sweden to buy Livonia and Riga from it and pledged to settle its issues with Russia by diplomatic means.

Duke Jacob stands out amongst other 17th century rulers not only for his ambitious plans and religious tolerance, which was very untypical in the Age of Absolutism, but also by his preference for peaceful means in resolving political issues. However, Jacob’s enterprises often did not match the actual capacities of his state and his excessive reliance on the promises of diplomatic and trade partners not infrequently led to great material losses. Duke Jacob may be truly admired for his daring, tenacity and activity, yet, when leaving this world on 31st December 1681, he placed his eldest son and heir to the throne, Friedrich Casimir (1650–1698), in a rather complicated internal political and economic situation.

The rule of Friedrich Casimir Kettler

Duke Ferdinand. Painting at the Gripsholm Castle in Sweden. Provided by Mārīte Jakovļeva, 2020.

Friedrich Casimir, together with the rest of the ducal family, had undergone captivity at the hands of the Swedes. Since the dangers of war had not subsided even after the signing of Oliva peace treaty as the Polish-Russian war went on (until 1667), for security reasons, Duke Jacob sent his heir to stay with the Elector of Brandenburg after their return to Courland. The Prince spent almost ten years in Berlin and Cleve, where he was under the care of the governor of Cleves Johann Maurice of Nassau (1604–1679). Apparently under the influence of Johann Maurice, who in 1671 had been appointed commander-in-chief of the Dutch States Army, Friedrich Casimir did not stay in Courland after his ‘gentleman’s tour’ but joined the Dutch Army together with several regiments that he himself had recruited. He took part in the French-Dutch War (1672–1674) and in The Hague on 5th October 1675, he married Johann Maurice’s niece Sophie Amelie (1650–1688). The following summer, the young couple moved to Courland, where Duke Jacob engaged his heir in the governance of the state. However, after his father’s death, Friedrich Casimir faced difficult tasks. The young duke had to exert great effort to settle relations with the landlords that in the last years of Jacob’s rule had become strained. The landlords refused to swear the oath of allegiance to Friedrich Casimir before all their complaints were reviewed. The parties reached an agreement only in 1684 when Friedrich Casimir signed a pledge to respect all the landlords’ rights and privileges and the landlords finally swore the oath of allegiance to him. Furthermore, in compliance with Jacob’s will, Friedrich Casimir had to pay his siblings huge amounts of money that he had to borrow abroad. Naturally, this was not an easy task, however, his relatives were not willing to wait and demanded the entire amounts bequeathed to them by the will at once. The duke had a particularly harsh dispute with his brother Ferdinand (1655–1737), which the Elector of Brandenburg and the King of Poland had to help resolve (see Bues 1995).

On the whole, Friedrich Casimir followed the economic and policy principles set by his father. For example, he reorganised the duchy’s metal industry following the model of Sweden, which at the time had a highly progressive metallurgical industry, and built ships not only in Ventspils, but also in Liepāja (as of 1677). The duke also tried to maintain his colony on Tobago island, which had been regained shortly before Jacob’s death, however, the great distance and financial problems made it difficult to grant the colony the necessary support. Although in the last decades of the 17th century the region was spared large-scale military conflicts, it was impossible to entirely avoid conflicts with the neighbours. The deepest discord was caused by the struggle of the Swedes against the unauthorised small parts of the coast of Courland under the inspiration of Riga, as the latter regarded the establishing of any new port apart from Liepāja and Ventspils as a violation of its privileges. In the spring of 1697, Friedrich Casimir received the so-called Grand Russian Embassy, which included Tsar Peter I who thus travelled incognito to Western Europe. Peter liked the kind welcome that he received in Courland much better than the unfriendly attitude demonstrated towards him in Riga and apparently this later contributed to the tsar’s relatively benevolent attitude towards the duchy in the context of the Great Northern War (1700–1721). A few months after the tsar’s visit, the Duchy of Courland was visited also by the Elector of Brandenburg Friedrich III (1657–1713; the future King of Prussia Friedrich I), whose sister Elisabeth Sophie (1674–1748) had become Friedrich Casimir’s second wife. During Friedrich Casimir’s rule, the existence of the Duchy of Courland as such was not threatened. However, the situation changed dramatically after his death on 22nd January 1698.

The first wife of Duke Friedrich Casimir, Sophie Amelie, Princess of Nassau-Siegen. Painting at the Gripsholm Castle in Sweden. Provided by Mārīte Jakovļeva, 2020.

The second wife of Duke Friedrich Casimir, Elisabeth Sophie, Princess of Brandenburg-Prussia. Painting by Gedeon Romandon (1691). Provided by Mārīte Jakovļeva, 2020.

Duke Friedrich Wilhelm. Engraving by Christoph Weigel (1710). Provided by Mārīte Jakovļeva, 2020.

Power struggles over the succession of the throne

Friedrich Casimir’s only son and heir to the throne Friedrich Wilhelm (1692–1711) was less than six years old at the time of his father’s death. This situation immediately triggered a massive political struggle for the guardianship of the young duke. Both the Dowager Duchess Elisabeth Sophie, who mobilised the support of Brandenburg-Prussia, and the late duke’s brother Ferdinand, who had spent a long time in the Polish-Lithuanian army and had good contacts at the Polish Court, aspired to the regent’s status. Ferdinand seemed to prevail, however the situation remained unstable. The power crisis was further deepened by the Great Northern War. On 22nd February 1700, when the King of Poland Lithuania and Elector of Saxony August II the Strong (1670–1733) used the territory of the duchy as a bridge-head for his attack on the Swedish Riga, Ferdinand was forced to abandon the policy of Courland’s neutrality. To maximally protect the duchy from the license of the Saxon troops and to gain August II’s support in his domestic policy struggles, in May 1700 Ferdinand entered the King’s military service. After the defeat of the combined Saxon and Russian forces at the Battle of Spilve on 19th July 1701, Ferdinand left Courland and the army and henceforth worked towards the de-occupation of the duchy by diplomatic means. He never returned to Courland. Elisabeth Sophie had left the duchy even earlier, together with her son, departing for Königsberg to attend the crowning ceremony of her half-brother, the Elector of Brandenburg Friedrich III as the King of Prussia in January 1701.

The Swedes quickly captured the entire territory of the duchy. The Swedish occupation lasted until mid-1709, with an interval in 1705/1706 when Russian troops arrived in Courland. Victory at Poltava (1709) allowed the Russian Tsar Peter I to concentrate his forces for the conquest of the Baltics and with the annexation of Livonia (the present-day Vidzeme region and Estonia) to Russia in 1710, Russia’s influence started to increase also in Courland.

Since at that time Peter I still had to reckon with the opinion of his allies, who at the same time were his competitors, in late 1709, Poland-Lithuania, Russia and Prussia agreed on keeping the existing status for the Duchy of Courland. However, to be allowed to ascend the throne of Courland, Friedrich Wilhelm, who had been raised in Germany, had to marry the niece of the Russian Tsar Peter I, Anna Ivanovna (1693–1740). Regrettably, the Duchy of Courland’s prospects of a more peaceful life were reduced to ashes when the young duke died on his way home from his wedding in Saint Petersburg in January 1711, leaving Anna Ivanovna a widow. On the tsar’s order Anna Ivanovna moved to Jelgava in 1716. A range of ducal manors, including Kuldīga, were allocated for her maintenance. The duchy, already ravaged by the war and plague, had to pay the Russians various tributes and the widow’s provision that was stipulated in the marriage contract. In turn, Ferdinand, who lived in Danzig (mod. Gdansk), did not recognise either his nephew, or his widow’s right to govern Courland and continued sending instructions to the board of senior councillors, which also sporadically tried to pursue its own policy. The duchy’s landlords also had split into several factions. Thus, the Duchy of Courland remained overwhelmed by political chaos, which had set in right after Duke Friedrich Casimir’s death.

Duke Ferdinand. Painting at the Gripsholm Castle in Sweden. Provided by Mārīte Jakovļeva, 2020.

Former Duchess of Courland Anna Ivanovna after becoming the ruler of Russia. Engraving by Georg Paul Busch (1730). Provided by Mārīte Jakovļeva, 2020.

The end of the Kettler dynasty

Since Ferdinand had no children, the issue of the future of the Duchy of Courland became complicated. Soon after the news of Duke Friedrich Wilhelm’s death had spread, there began a search for the next claimant to the throne. Saxony, Brandenburg-Prussia, Hessen-Kassel and several other states actively advanced their own candidates, however, Russia dictated the rules, putting forward the demand that the pretender to the throne of Courland had to marry Anna Ivanovna. The interested parties could not agree on any of the candidates, whose number had reached 17 by 1724 and continued to grow. The election of August II’s son, Prince Maurice of Saxony (1696–1750), as duke by the diet (landtag) on 5th July 1726 gave Saxony only ephemeral hope of founding their dynasty in Courland, as it was contested both by Russia and a group of Polish-Lithuanian landlords who were not interested in the consolidation of royal power and would have preferred to see the duchy as a province of Poland-Lithuania. Although Maurice came to Jelgava and managed to win Anna Ivanovna’s favour, he failed to become Ferdinand’s successor to the throne as in 1727 the Polish-Lithuanian Sejm annulled the landtag’s decision and Maurice had to flee abroad to escape being arrested by the Russians.

The fate of the duchy was decided by the growth of Russian influence in Poland. During the so-called War of the Polish Succession (1733–1735), Russia forced the Polish-Lithuanian Sejm to elect August III (1696–1763) as king. Under Russian pressure, in 1736, the Sejm also revoked its earlier decision on the incorporation of Courland and accepted the duchy’s right to elect a new duke after Ferdinand’s death. This happened very soon after, as Ferdinand died in Danzig on 4th May 1737. Five weeks later, the landlords of Courland gathered in Jelgava and elected Anna Ivanovna’s favourite Ernst Johann Biron (1690–1772) as duke. Anna Ivanovna herself had become the Empress of Russia in 1730. Biron came from the von Bühren family which once had been denied entry in the Adelsmatrikul of Courland. However, neither Ernst Johann, who ruled in 1737–1740 and 1763–1769, nor his son Peter Biron (1724–1800), who sat on the throne in 1769–1795, managed to win stable ducal power. This was due not only to resistance from the landlords, but also to internal political developments in Russia, as a result of which in late 1740 Ernst Johann was arrested and exiled together with his family for more than 20 years. During this time, the highest local authority in the duchy, which formally still retained its vassalage to Poland-Lithuania, was represented by the senior councillors, but the decisive role was played by the resident i.e. the authorised minister of Russia. In 1758, with Russia’s support, the throne of Courland was granted to the Prince of Saxony Carl (1733–1796) who was the son of King August III of Poland. However, soon after Catherine II’s (1729–1796) accession to the Russian throne in 1762, the attitude of Russia changed again and in April 1763 Carl had to leave Courland.

Duke Ernst Johann Biron. Latvian State History Archive, fund ID 640, description ID 2, case ID 262.

Duke Peter Biron. Painting by F. H. Barisien at Rundāle Castle Museum. Provided by Mārīte Jakovļeva, 2020

While all of the above-named challenges occurred on the political scene, Kuldīga registered its fastest expansion. Whereas the previous expansions mostly reflected on the evolution of the society living in Kuldīga, the 18th century expansions highlight the increasing interchange also with other towns in the Duchy, as the roads leading to Ventspils (in the north), Aizpute and Liepaja (in the west) and Skrunda and Jelgava (in the south) were paved. A distinct town centre and new roadways along with new buildings were constructed and determined the intermodal shape of the town. In this time, the density of construction increased significantly along the main new streets.

The expansion of Kuldīga’s urban layout in the 18th century. Schematic representation by Inta Jansone according to the research “Kuldīga. Pilsētbūvniecība un arhitektūra”, 2020 Intas Jansones shematisks attēlojums atbilstoši pētījuma “Kuldīga. Pilsētbūvniecība un arhitektūra” rezultātiem, 2020.

The dissolution of the Duchy

Plate with the name of the street “Louisenstraße” at Bad Homburg, former capital of the Hessen-Homburg Landgrafschaft. Photo by Mārīte Jakovļeva, 2020.

In the final years of the duchy the struggle between the duke and the landlords’ opposition continued and, moreover, the town dwellers also started to speak up for their political rights in 1790, founding a Burgher’s Union (Bürgerliche Union). But the greatest concern among the ruling circles of the duchy was caused by an uprising led by Tadeusz Kościuszko (1746–1817) that started in Poland in 1794 and soon spread to Courland as well. In fear of the rebels and under political pressure from Russia, on 18th March 1795, the Diet of Courland adopted a declaration on surrendering to Russia. Ten days later, Duke Peter signed his abdication in Saint Petersburg and on 26th April 1795, Catherine II declared Courland and Semigallia a province of the Russian Empire. Thus, the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia ceased to exist. It should be noted that the surrendering of the Duchy of Courland to Russia was only seemingly voluntary, as in fact, its annexation was already planned during the Third Partition of Poland.

Remnants of Courland times

The period of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia (1562–1795) marks an important and striking page in the history of Latvia. The period under discussion largely saw the formation of the population structure in the region and the network of churches that stayed in place until the 20th century, as well as the development of the typical Courlander mentality. After the collapse of Livonia, the duchy represented local statehood, in contrast to the other territories of present-day Latvia that came under direct subjugation to neighbouring powers. However, the complicated geopolitical situation that the duchy faced, serving as a buffer zone between the neighbouring powers – Poland-Lithuania, Sweden and Russia – as well as the constant challenge from the part of the Courlandish landowners eventually led to the liquidation of the duchy. However, thanks to the activities of the Kettler and Biron dukes, the name of Courland became known both in Europe and in other parts of the world. The Courlanders’ extensive trade, cultural and family contacts show that, in the early modern period, Courland was not as provincial as it gradually became as part of the Russian Empire. The “footprints” of Courland can be found in place names on Tobago and in many places in Europe, for example, in Bad Homburg, the capital of the former Hessen-Homburg Langraviate there is a “Luise Street” (Louisenstraße), named in honour of Duke Jacob’s daughter Luise Elisabeth (1646–1690). The interior items and paintings commissioned by the Dukes of Courland are now part of the museums and private collections of many countries. A “Courland’s Competition” established by Duke Peter Biron for the best artwork was held from 1785 to 1946 in the Art Academy of Bologna (Academia Clementina) in Italy. Today, the Royal Porcelain Manufacture in Berlin decorates various objects with the so-called Courlandish ornament (Kurland-Dekor). Its origin is associated with a set, which was commissioned in 1787 by Duke Peter Biron for his newly acquired Friedrichsfelde Palace.

A dish from the “Courland set” (18th century) at Rundāle Palace Museum. Photo by Mārīte Jakovļeva, 2020.

Political Development after the dissolution of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia

Throughout its history, the modern Latvian territory was subject to many political changes. Since 1561, the beginning of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Swedish Empire and Russia fought over this area in the Baltics. The citizens of Courland were constantly confronted with wars between regional opposing powers. After more than 230 years under ducal rule, the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia was dissolved and it became a Russian province in the course of the third partition of Poland in 1795. It was the last territory of modern Latvia to be annexed to the Russian Empire. The subsequent period was to last for almost 130 years: Latvia officially belonged to Russia until the end of World War One.

Kuldīga in the Russian Empire (1795-1918)

In 1795, Russia, Austria and Prussia signed an agreement on the third partition of Poland. Under the terms of this agreement, the former Polish province – the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia – came under Russian rule. With this annexation of the duchy to Russia, the entire territory of modern Latvia came under its control: Vidzeme and Riga were annexed to Russia immediately after the Great Northern War in 1721 and Latgale during the first partition of Poland in 1772.

Within the Russian Empire, the former Livonian territory formed the Baltic Governor-General's area, which consisted of three provinces - the Estonian province, the Vidzeme province and the Courland province. Each province was governed by a Governor, who in turn was subordinated to the Governor General of the Baltic provinces, who resided in Riga (until 1876, when the post of governor general was abolished) (Švābe 1962, 24 pp). The province of Courland was formed by the former territory of the duchy, and the palace of the dukes in Jelgava became the seat of the Governor. The province administration, such as the Supreme Court, was also placed in Jelgava.

After the annexation of the Baltic territories to the Russian Empire, a long process began to integrate these three different territories into the empire's administrative, judicial and administrative structure, each with its own administrative structure and historically privileged German landlords. This process was entirely completed only in 1889, when the Russian judicial system and the corresponding laws were extended to the Baltic territories (Švābe 1962, 21-27).

During this time, very significant changes took place in the structure of society. Serfdom was abolished (in Courland in 1817, in Vidzeme in 1819, and in Latgale in 1861) and the peasants became personally free, although their cultivated land and houses remained the property of the landlords. The population of the cities grew rapidly, industry and transport developed. Education began to be available to the masses, including Latvians.

Within the Russian Empire, the town of Kuldīga retained its town administration, which had already been established in the Middle Ages, and the rights of the city of Riga, which had been modified over the centuries and slightly adapted to local conditions, for a long time. At the end of the 18th century, the Town Council of Kuldīga was formed by seven members. In general, the municipality was provided by the Council, the Large Guild or merchants' association and the Small Guild or craftsmen's association. Such an arrangement existed in Kuldīga until 1870, when the laws of Russian cities were applied to it (Švābe 1962, 245-248).

For a long time, the position of the superintendent, respectively the Chief Judge, and the Precinct of the Supreme Court of Kuldīga also continued to exist. In the 19th century, Kuldīga was one of the five highest judicial districts, the rest were located in Sēlpils, Jelgava, Tukums and Aizpute. It was only with the reform of the police and the reform of the judiciary (actually their assimilation to the laws of the empire) in 1888 and 1889, respectively, that the positions of the superintendent were abolished and converted into District Governors. However, this change only meant that a large number of landlords, former superintendents, continued the same duties, only in the role of tsarist officials (Švābe 1962, 483-503).

Kuldīga lost more and more of its central status in the Russian Empire. The administrative centre moved permanently to Jelgava and several other cities began to overtake Kuldīga in their development. Shortly after joining the empire, in 1798, Kuldīga was the fourth largest city of Courland after Jelgava, Liepāja and Jēkabpils, with 1352 inhabitants. In 1856, the population of Kuldīga had grown to 4,818, but it was only the fifth largest city after Jelgava, Liepāja, Aizpute and Bauska (Švābe 1962, 261). Waterways, which had previously dominated trade, were replaced by rail from the middle of the 19th century, and cities near railway lines grew accordingly. The first railway lines built in Courland did not affect Kuldīga. The Venta was too shallow for transporting the quantities of goods necessary for industry and the surrounding dirt roads were in poor condition (Krastiņš 2013, 224f). As a result of these factors, the city's development slowed down considerably, which had a positive effect on the preservation of the duchy’s legacy.